Portfolio rebalancing: investors’ safe asset substitution patterns

- THE ECB BLOG

Portfolio rebalancing: investors’ safe asset substitution patterns

6 January 2025

By Tsvetelina Nenova

This is the first post in our series featuring the work of the ECB’s 2024 Young Economist Prize finalists. Tsvetelina Nenova won with the research highlighted in this post.

When returns on safe assets fall, investors move some of their money to riskier assets. This ECB Blog shows: US Treasuries are replaced by global bonds, while substitutes for Bunds are mostly from Europe. This effect is smaller in times of market stress.

Investors regularly change the makeup of their portfolios to hold a mixture of risky and safe assets. The most prominent of the latter are US and German government debt securities (Treasuries and Bunds), as they benefit both from large markets and from top credit ratings. Sometimes these assets become less attractive – for example, due to a change in monetary policy – making investors revise their position. This process is called portfolio rebalancing, and central banks count on it for the transmission of their monetary policy to the economy. When central banks lower their policy interest rates, for example, this lowers first and foremost the returns on safe assets. This creates an incentive for investors to accept a little bit more risk to get higher returns, which eventually can help to ease the financing conditions for investments in the economy. In this Blog post I discuss the strength and composition of this spillover effect, whether it’s global or regional, and how it changes in times of crisis.

I find that investors behave differently in the cases of Treasuries and Bunds. When Treasury returns fall, for instance because the Federal Reserve is expected to cut interest rates, investors tend to shift their portfolios toward riskier corporate and emerging market bonds. In the euro area, German Bunds are the primary safe asset. Investors also reduce their Bunds holdings when their returns fall. However, they go for sovereign bonds by other euro area governments rather than spreading their money across the globe or to domestic corporate bonds.

This rebalancing behaviour also changes over time. Investors become more reluctant to swap safe assets with risky ones during a financial crisis. This has important implications for how central banks design asset purchase programmes. My findings suggest that if central banks buy only safe assets in times of market stress, such purchases affect the economy less than in normal times.

Let’s take a closer look at these different types of rebalancing behaviour.

How to measure rebalancing?

But first, how do we measure the strength and composition of portfolio rebalancing in international bond markets? I estimate two connected measures. Each bond’s own demand elasticity measures how much the portfolio weight investors allocate to that bond falls when the expected return on the same bond falls relative to other bonds. In other words, own demand elasticity captures by how much investors allocate money away from a bond when it promises lower returns.

I take monetary policy announcements by the US Federal Reserve and ECB that affect bonds with long vs short maturities as a source of such changes in returns. For instance, in March 2009 the Fed announced an expansion of its Large-Scale Asset Purchases including US Treasuries[1]. As this lowered the expected returns on these bonds, investors in my sample reduced the portfolio weight allocated to US Treasuries. Such events allow me to estimate the own demand elasticity of bond portfolio weights relative to changes in the same bond’s returns.

Of course, if investors are reducing the portfolio weight of the affected bond, they must be increasing the portfolio weights of other assets. The composition of this rebalancing is then captured by the substitution elasticity of any other bond in response to the change in the return of the affected bond.

I estimate these elasticities using portfolio data from mutual funds located either in the euro area or the US. This investor group (i) has grown rapidly since the global financial crisis of 2008-09; (ii) rebalances portfolios more actively than more regulated investors such as pension funds and insurers; and (iii) accounts for much of cross-border portfolio investments in bonds. The data set covers the portfolios and characteristics of over 11,000 mutual funds between 2007 and 2020, as well as extensive information on the returns and features of thousands of different international government and corporate bonds.

Demand for safe assets is less elastic

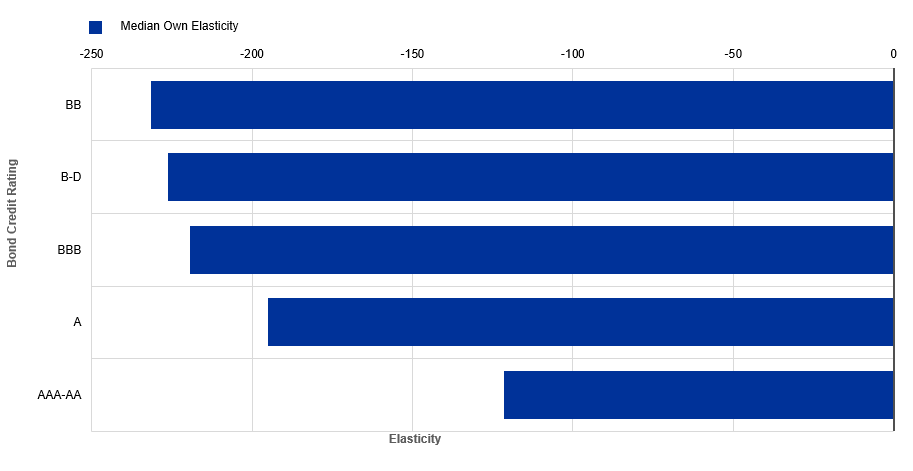

I find that demand for safe assets is less elastic than for other bonds (Chart 1). Investors are less willing to part with their Treasuries and Bunds despite declining returns than they are when risky bond returns decline. There are many reasons why investors may respond less to changes in safe asset returns. For instance, holding safe assets may offer additional benefits: their markets are more liquid, they can be pledged as collateral or used to satisfy regulatory requirements. What this low own elasticity means for monetary policy makers is that inducing portfolio rebalancing away from safe assets requires a bigger fall in their return.

Chart 1

Own demand elasticities for sovereign bonds of different credit quality

Sources: Own calculations based on Morningstar and Refinitiv data.

Notes: Each bar shows the median reduction of the portfolio weight of bonds with a credit rating as indicated on the vertical axis in response to a decline in their own expected return. For example, a 100 basis point reduction of the expected return on an A-rated sovereign bond is estimated to lead to a 195 basis point decline in its portfolio share across all investment fund portfolios covered.

Where do investors go? Global vs. regional substitution

Even though lower than for other bonds, the own demand elasticities of safe assets still imply considerable portfolio rebalancing. And the composition of this rebalancing matters. The substitution elasticities for the most important safe assets of the US and euro area, US Treasuries and German Bunds, paint two different pictures of rebalancing behaviour.

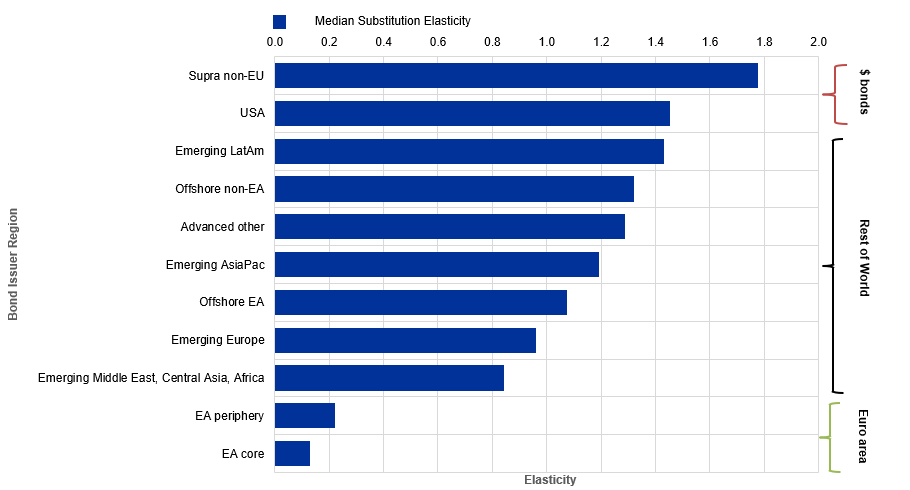

In the case of Treasuries, investors move their money to riskier US dollar-denominated bonds such as those issued by supranational organisations or US corporates. They also add more emerging market sovereign bonds to their holdings, especially of Latin American countries. The bond market reach of US safe asset shocks is thus global, but also associated with shifts in risk-taking domestically (Chart 2).

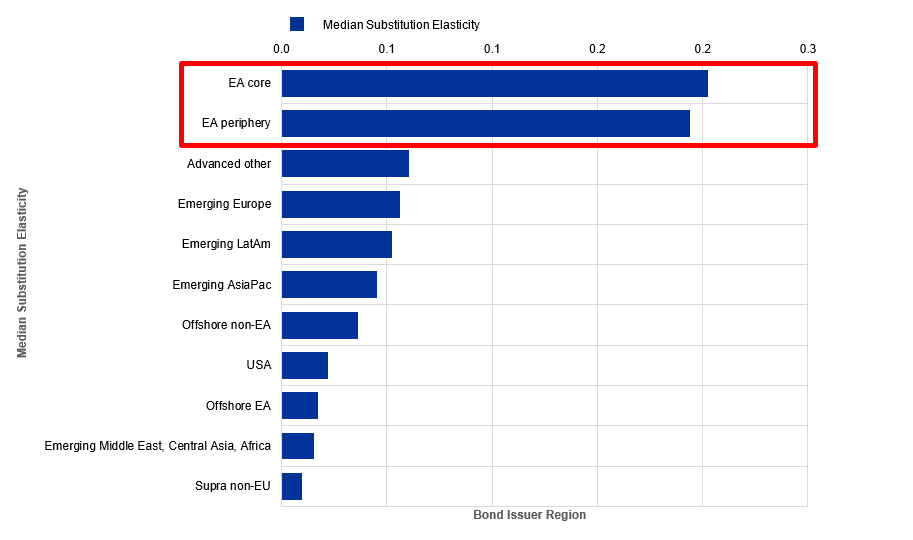

Euro area safe assets are different: changes in German Bund returns see portfolio rebalancing primarily within the euro area sovereign debt market. The largest (absolute) substitution elasticities with respect to Bund returns are distributed across a diverse set of euro area issuers. Meanwhile, spillovers outside the euro area are limited (Chart 3).

Also worth noting but less surprising is that the magnitude of overall rebalancing in Chart 3 is about a tenth of the rebalancing after a change in US Treasury returns in Chart 2. This simply reflects the fact that the smaller share of German Bunds in investor portfolios induces smaller rebalancing flows for the same change in returns.

Chart 2

Substitution elasticities by bond issuer region with respect to changes in expected returns on short-term US Treasuries

Sources: Own calculations based on Morningstar and Refinitiv data.

Notes: Each bar shows the median increase in the portfolio weight of bonds of the issuer region indicated on the vertical axis in response to a decline in the expected return on short-term US Treasuries. For example, a 100 basis point reduction of US Treasury expected returns is estimated to lead to a 1.43 basis point median increase in the portfolio shares of Latin American sovereign bonds across all investment fund portfolios covered.

Chart 3

Substitution elasticities by bond issuer region with respect to changes in expected returns on short-term German Bunds

Sources: Own calculations based on Morningstar and Refinitiv data.

Notes: Each bar shows the median increase in the portfolio weight of bonds of the issuer region indicated on the vertical axis in response to a decline in the expected return on short-term German Bunds. For example, a 100 basis point reduction of German Bunds expected returns is estimated to lead to a 0.2 basis point median increase in the portfolio shares of other euro area core sovereign bonds across all investment fund portfolios covered.

These different rebalancing patterns by international investment funds imply that monetary policy news coming from the Fed which causes shocks to US Treasury returns have global spillover effects. Meanwhile, ECB monetary policy likely has more limited spillovers outside the EU through such portfolio rebalancing.

Portfolio rebalancing is weaker during financial crises

Rebalancing between safe and risky assets is not static over time, however. I also document that the degree of substitution away from Treasuries and Bunds decreases in times of financial market stress, meaning investors hold on to safe assets more tightly.

Why is this time variation important? One direct implication is that central banks should carefully design the composition of asset purchases and sales programmes. For instance, were the central bank to buy exclusively safe assets when markets are in turmoil, transmission to the broader economy through investors’ portfolio rebalancing would be more limited than during normal times. This is consistent with evidence that direct purchases of the distressed assets (e.g. mortgage-backed securities in the US[2]; or vulnerable government bonds at the height of the European debt crisis[3]) were more effective than purchases of safe government bonds during more tranquil market conditions.

Yet, important nuances emerge in this time variation in portfolio rebalancing in the two currency areas:

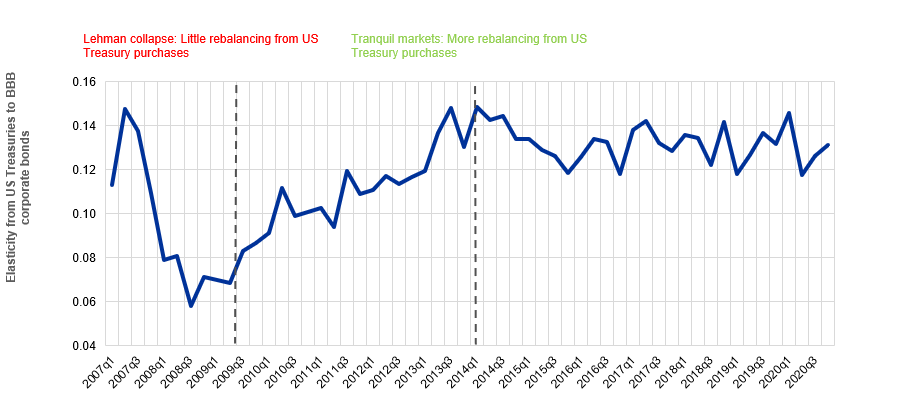

- In the US, it is rebalancing from the safe asset to US risky corporate bonds in particular that halves during the global financial crisis of 2008-09 (Chart 4). For the Fed, this reduced willingness of investment funds to rebalance towards risky assets implies that monetary easing involving central bank purchases of safe assets would be less effective at improving domestic corporate financing conditions in a financial crisis.

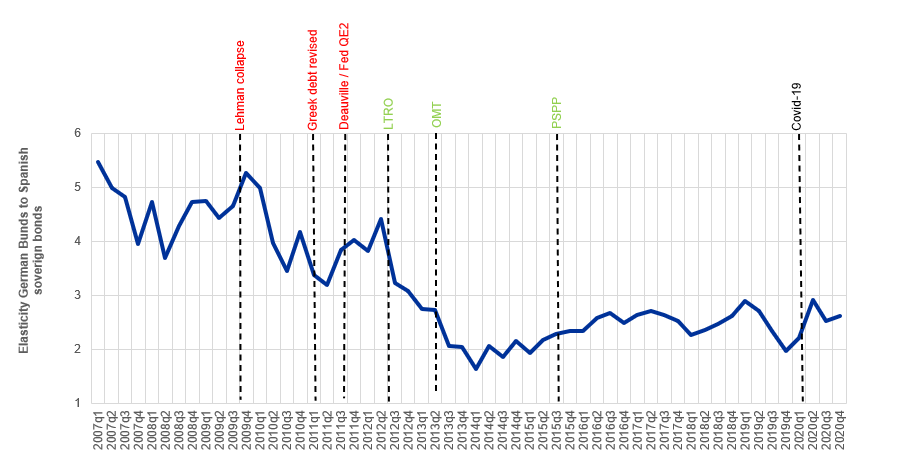

- In the euro area, substitutability between German Bunds and other euro area government bonds declines in times of stress. This is evident in Chart 5, beginning with the unfolding of the Eurozone debt crisis from 2010 on. Investors flee to the safety of German Bunds and increase regional fragmentation, implying an uneven distribution of the effects of monetary policy across the Eurozone.

Chart 4

Time variation in substitution between US Treasuries and BBB-rated US corporate bonds

Sources and Notes: Own calculations based on Morningstar and Refinitiv data.

Chart 5

Time variation in substitution between German and Spanish government bonds

Sources and Notes: Own calculations based on Morningstar and Refinitiv data.

Conclusion

Textbook economics assumes that a shift in the expected return on safe assets transmits to riskier assets, and ultimately to borrowing costs more broadly. This occurs partly through the rebalancing of private investors’ portfolios away from (the lower yielding) safe assets and towards riskier (higher return) assets. My results imply that this transmission channel might not always be as broad-based and effective as the theory would suggest: transmission of monetary policy through substitution from safe to risky assets differs depending on the specific safe asset and changes over time. My finding that the portfolio rebalancing channel of monetary policy weakens during financial distress calls for careful and state-contingent calibration of the composition of central bank asset purchases.

The views expressed in each blog entry are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the European Central Bank and the Eurosystem.

Check out The ECB Blog and subscribe for future posts.

For topics relating to banking supervision, why not have a look at The Supervision Blog?

Related topics

Disclaimer

Please note that related topic tags are currently available for selected content only.