Geopolitics and trade in the euro area and the United States: a de-risking of import supplies?

Prepared by Ivelina Ilkova, Laura Lebastard and Roberta Serafini

Published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 5/2024.

In recent years, a series of adverse shocks has highlighted vulnerabilities related to the sourcing of imported goods. In response, some firms in both the euro area and the United States have changed (or are planning to change) their sourcing strategies to improve supply-chain resilience.[1] Based on detailed product-level data, this box analyses the extent to which and how the euro area and the United States have modified their sourcing strategies since 2016 – when geopolitical considerations began to play a stronger role in trade relations and de-risking concerns arose[2] – and the potential impact on import prices. It focuses on two different, but not mutually exclusive, sourcing strategies aimed at fostering supply-chain resilience and addressing national security concerns: diversification (increasing the number of supplier countries) and rebalancing (reducing the market share of the main supplier country).[3]

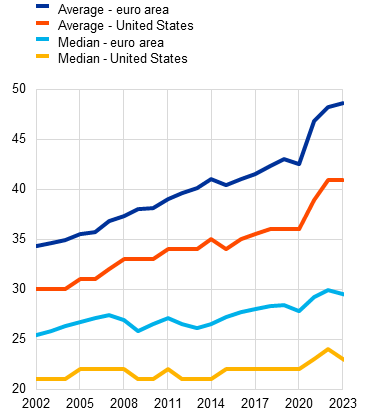

Over the past decade, the euro area has progressively diversified import sources, although there is no sign that this process has accelerated compared with the past. Since 2016 the euro area has gradually increased the number of sourcing countries per product, including for goods of strategic importance,[4] with a slight acceleration observed since the pandemic (Chart A, panel a). This appears, however, to be the continuation of a process that had been ongoing in the euro area since the beginning of the century. By contrast, diversification has been less evident in the United States.

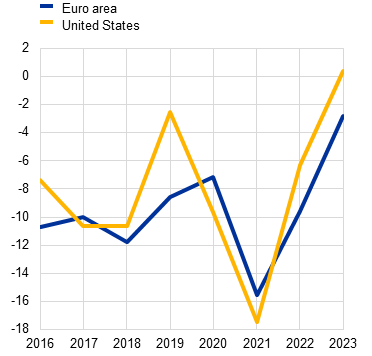

Diversification has, however, increasingly had a geopolitical dimension, with both the euro area and the United States diversifying imports of products sourced relatively more from geopolitically distant countries. We assessed the extent to which this diversification has a geopolitical dimension by classifying supplier countries as geopolitically close (for example, the G7 countries, EU Member States, Australia, South Korea and Türkiye) and geopolitically distant (for example, China, Russia, Iran, North Korea and Syria).[5] Chart A, panel b), presents the results of an event study estimating whether, for a given imported product, having a geopolitically distant country as the main supplier affected the overall number of supplier countries compared with products mainly sourced from a geopolitically close country.[6] The results suggest that diversification of import sources since 2016 has been significantly stronger for products imported relatively more from geopolitically distant countries, with its level rising in both regions under review, particularly after 2021.

Chart A

Diversification of sourcing countries for the euro area and the United States

|

a) Number of sourcing countries per product |

b) Diversification when the main supplier country is geopolitically distant |

|---|---|

| (averages and medians) | (differences in the number of sourcing countries compared with goods sourced from geopolitically close countries) |

|

|

Sources: Trade Data Monitor and ECB calculations.

Notes: Product is defined at the most detailed product characteristics level enabling cross-countries comparison (six-digit level of the World Customs Organization Harmonized System classification). Panel b) shows the results of an event study comparing the number of sourcing countries for a given product when the main sourcing country is a geopolitically distant country rather than a geopolitically close country. The data used for the euro area regression exclude intra-euro area trade. The reference year is 2016. The shaded areas indicate the 95% confidence intervals.

While some diversification of import sources has been under way for a number of years, evidence of a shift in the reliance of the euro area and the United States on geopolitically distant countries is more mixed. Aggregate data indicate that China’s market share in euro area imports has risen by 3 percentage points since 2016, whereas it has declined by 11 percentage points in US imports. Since 2022 the euro area has had greater exposure to China compared with the United States. In the case of Russia, both the euro area and the United States have decreased their import market shares, in line with the sanctions imposed and the related embargoes. However, sourcing from China and Russia apart, evidence of rebalancing is more limited: aggregate import shares from geopolitically distant countries have remained stable for both the euro area and the United States, with neither region significantly shifting their imports away from these countries.

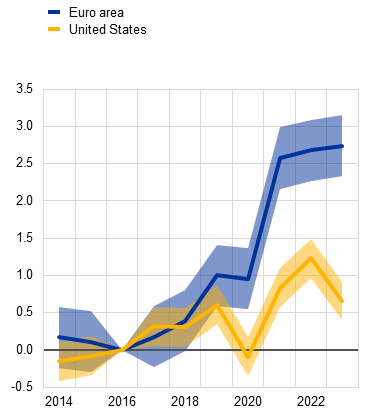

Evidence at the product level underlines that rebalancing away from a main supplier nation is limited. Focusing on strategic goods, we compared import developments for products mostly sourced from a geopolitically distant country and for those mostly sourced from a geopolitically close country. The results of an event study point to limited evidence of a substantial rebalancing by the euro area or the United States away from geopolitically distant countries (Chart B).[7]

Chart B

Change in the importance of a main sourcing country for strategically important goods when it is a geopolitically distant country for the euro area and the United States

(percentage differences compared with the import level of goods sourced from geopolitically close countries)

Sources: Trade Data Monitor and ECB calculations.

Notes: The chart shows the results of an event study comparing the levels of imports of strategically important goods from countries that are geopolitically close and geopolitically distant . The database includes import volumes data for strategically important goods from all trading partners at the six-digit level of the World Customs Organization Harmonized System (HS) classification. Data for goods falling under Chapter 27 of the HS classification (mineral fuels, mineral oils and products of their distillation; bituminous substances; mineral waxes) were excluded. The data used for the euro area regression exclude intra-euro area trade. The reference year is 2016. The shaded areas indicate the 95% confidence intervals.

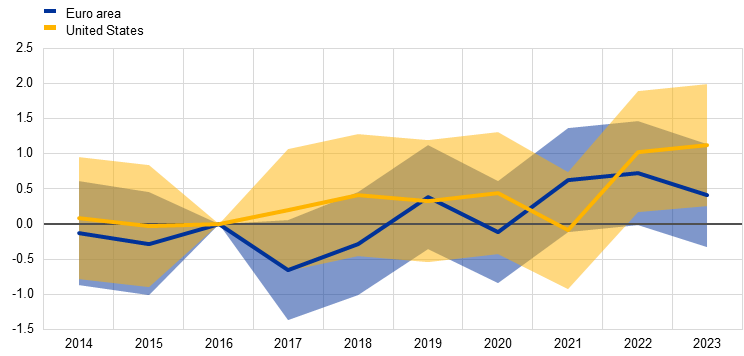

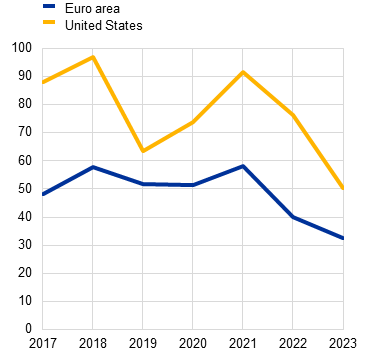

The implications for import prices differ depending on which sourcing strategy dominates. For the same product, suppliers from new sourcing countries tend to be more expensive than existing suppliers (Chart C, panel a). However, the impact on aggregate import prices is small: on average over the period 2016-23, the flow of products from new countries accounted for a small share of total imports (0.2-0.3%), suggesting only a limited impact on aggregate prices.

For those products for which either the euro area or the United States has changed its main supplier country, rebalancing seems to be aimed mostly at reducing costs, rather than enhancing supply-chain resilience or addressing national security concerns. Rebalancing away from the main supplier country has primarily shifted imports towards cheaper sourcing countries, both for the euro area and the United States. On average, since 2016 the euro area and the United States have tended to rebalance imports towards cheaper sources, although there is some evidence of a change after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, when both shifted towards relatively more expensive sourcing countries (Chart C, panel b). Indeed, shifting imports from a main geopolitically distant supplier towards a geopolitically close supplier is associated with a median price increase of 30% and 40% in the euro area and the United States respectively. Shifting within a group of geopolitically close countries has a broadly neutral impact on import prices.

Chart C

Import price implications of euro area and US de-risking strategies

|

a) Between new and pre-existing product-country flows |

b) Between sourcing countries whose import shares increased and those that did not |

|---|---|

| (percentage differences, median of HS6 products) | (percentage differences, median of HS6 products) |

|

|

Source: Trade Data Monitor.

Notes: Panel a) shows the difference in price between a product from new sourcing countries (i.e. a product not imported from the sourcing country in the previous year) and the same product from pre-existing sourcing countries (i.e. a product already imported from the sourcing country in the previous year). To avoid bias resulting from occasional importers, only product-countries still being imported from in the subsequent year (except for 2023) are included. Panel b) shows the difference in price between a product from sourcing countries for which the market share has increased (in comparison with the previous year) and the same product from sourcing countries for which the market share has decreased or stagnated. HS6 stands for the six-digit level of the World Customs Organization Harmonized System classification.

-

See EIB Investment Survey – European Union Overview, European Investment Bank, 2023, and the box entitled “Global production and supply chain risks: insights from a survey of leading companies”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 7, European Central Bank, 2023.

-

In 2016 significant trade tensions emerged between the United States and China, marking the start of major US trade shifts. While that year might not hold the same significance for the euro area, which saw more impactful changes after 2019, starting the analysis in 2016 ensures a common period of comparison. This approach helps to capture key events that affected the United States and the euro area and provides a clearer understanding of how trade patterns evolved differently in the two regions. The results hold true if the analysis for the euro area starts in 2019 instead of 2016.

-

While not being the focus of this analysis, export strategies may also change in response to geopolitical tensions, in terms of relative reliance on a geopolitically distant customer base.

-

Strategic goods are defined as specified in the list in “Strategic dependencies and capacities”, Commission Staff Working Document, No 352, European Commission, 2021. The European Commission identified strategic dependencies related to specific imported inputs based on three indicators: concentration, measured based on the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index and the market shares of the extra-EU supplying countries; demand importance, calculated as the share of extra-EU imports in total EU imports; and substitutability, calculated as the ratio of extra-EU imports to total EU exports. For the United States, we constructed a similar set of products, adapting the European Commission methodology to the US data.

-

Geopolitically close and distant countries are defined according to their vote in the United Nations on sanctions against Russia – UN General Assembly Resolution ES-11/3. Abstaining countries are considered neutral and assigned to the geopolitically close group. The approach of identifying countries’ geopolitical similarities based on how they have voted in the United Nations is in line with Campos et al., “Geopolitical fragmentation and trade”, Journal of Comparative Economics, Vol. 51, No 4, 2023, pp. 1289-1315, and the box entitled “Friend-shoring global value chains: a model-based assessment”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 2, European Central Bank, 2023.

-

This is estimated separately for the euro area and the United States applying the following formula: , where the dependent variable is the number of sourcing countries for the six-digit level of the World Customs Organization Harmonized System classification product i at time t, and k is the number of years relative to 2016. The treatment group is the set of products whose main supplier was a geopolitically distant economy in 2014-16, whereas the control group is the set of products whose main sourcing country was a geopolitically close economy in 2014-16. The formula allows for product and time-specific fixed effects.

-

The chart shows the estimated of the mirror regression of Chart A, panel b): , where the dependent variable is the natural logarithm of imports from the main sourcing country j to the euro area of product i at time t.