EU Economic Bulletin Issue 4, 2023. Economic, financial and monetary developments

Economic, financial and monetary developments

Overview

Inflation has been coming down but is projected to remain too high for too long. The Governing Council is determined to ensure that inflation returns to its 2% medium-term target in a timely manner. It therefore decided at its meeting on 15 June 2023 to raise the three key ECB interest rates by 25 basis points.

The rate increase reflects the Governing Council’s updated assessment of the inflation outlook, the dynamics of underlying inflation, and the strength of monetary policy transmission. According to the June 2023 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area headline inflation is expected to average 5.4% in 2023, 3.0% in 2024 and 2.2% in 2025. Indicators of underlying price pressures remain strong, although some show tentative signs of softening. Staff have revised up their projections for inflation excluding energy and food, especially for this year and next year, owing to past upward surprises and the implications of the robust labour market for the speed of disinflation. They now see it reaching 5.1% in 2023, before it declines to 3.0% in 2024 and 2.3% in 2025. Staff have slightly lowered their economic growth projections for this year and next year. They now expect the economy to grow by 0.9% in 2023, 1.5% in 2024 and 1.6% in 2025.

At the same time, the Governing Council’s past rate increases are being transmitted forcefully to financing conditions and are gradually having an impact across the economy. Borrowing costs have increased steeply and the growth in loans is slowing. Tighter financing conditions are a key reason why inflation is projected to decline further towards target, as they are expected to increasingly dampen demand.

The Governing Council’s future decisions will ensure that the key ECB interest rates will be brought to levels sufficiently restrictive to achieve a timely return of inflation to the 2% medium-term target and will be kept at those levels for as long as necessary. The Governing Council will continue to follow a data-dependent approach to determining the appropriate level and duration of restriction. In particular, its interest rate decisions will continue to be based on its assessment of the inflation outlook in light of the incoming economic and financial data, the dynamics of underlying inflation, and the strength of monetary policy transmission.

The Governing Council confirmed that it would discontinue the reinvestments under the asset purchase programme (APP) as of July 2023.

Economic activity

The global economy started this year on a stronger footing than in the fourth quarter of 2022 thanks to the reopening of the Chineseeconomy and the resilience of labour markets in the United States. Global activity was mainly driven by the services sector, whereas manufacturing output remains relatively subdued. The fallout from the US banking sector woes in early March led to a brief period of acute stress in global financial markets. Since then, most asset prices have recovered the losses recorded during that period, while financial market participants also revised down their expectations for the future path of the Federal Reserve System’s monetary policy tightening. Nonetheless, lingering uncertainty is adding to global growth headwinds, including high inflation, tightening in global financial conditions and geopolitical tensions. Against this backdrop, the global growth and inflation outlook in the June 2023 projections remains broadly unchanged compared with the March 2023 ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area. The small upward revision to global growth in 2023 is mainly related to the stronger than previously expected recovery in demand in China in the first quarter, which was partially offset by the adverse impact of tighter financial and credit conditions in the United States and other advanced economies. The inflation outlook has been revised slightly upwards for 2024 against the backdrop of tight labour markets and still high wage growth in advanced economies, while lower commodity prices explain a small downward revision to projected inflation for 2023. World trade is projected to grow at a much slower pace than real GDP this year, as the composition of global demand has become less trade-intensive. The outlook for world trade for 2023 was revised down, albeit largely on account of sizeable negative carry-over effects from the fourth quarter of 2022 and weak outturns in major economies in the first quarter.

The euro area economy has stagnated in recent months. As in the fourth quarter of last year, it shrank by 0.1% in the first quarter of 2023, amid a drop in private and public consumption. Economic growth is likely to remain weak in the short run but strengthen in the course of the year, as inflation comes down and supply disruptions continue to ease. Conditions in different sectors of the economy are uneven: manufacturing continues to weaken, partly owing to lower global demand and tighter euro area financing conditions, while services remain resilient.

The labour market remains a source of strength. Almost a million new jobs were added in the first quarter of the year and the unemployment rate stood at a historical low of 6.5% in April. The average number of hours worked has also increased, although it is still somewhat below its pre-pandemic level.

According to the June 2023 projections, the economy is expected to return to growth in the coming quarters as energy prices moderate, foreign demand strengthens and supply bottlenecks are resolved, allowing firms to continue to work through their significant order backlogs, and as uncertainty – including that related to the recent banking sector stress – continues to recede. Furthermore, real incomes are set to improve, underpinned by the robust labour market, with unemployment hitting new historical lows over the projection horizon. The ECB’s monetary policy tightening will increasingly feed through to the real economy. Together with the gradual withdrawal of fiscal support, this will weigh on economic growth in the medium term. Overall, annual average real GDP growth is expected to slow down to 0.9% in 2023 (from 3.5% in 2022), before rebounding to 1.5% in 2024 and 1.6% in 2025. Compared with the March 2023 projections, the outlook for GDP growth has been revised down by 0.1 percentage points for 2023 and 2024, reflecting mainly tighter financing conditions. GDP growth in 2025 remains unchanged, as these effects are expected to be partly offset by the impact of higher real disposable income and lower uncertainty.

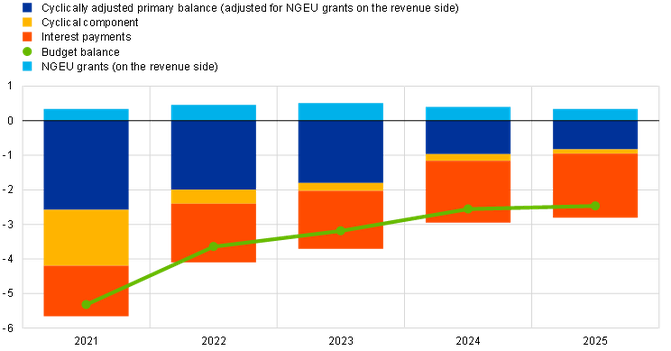

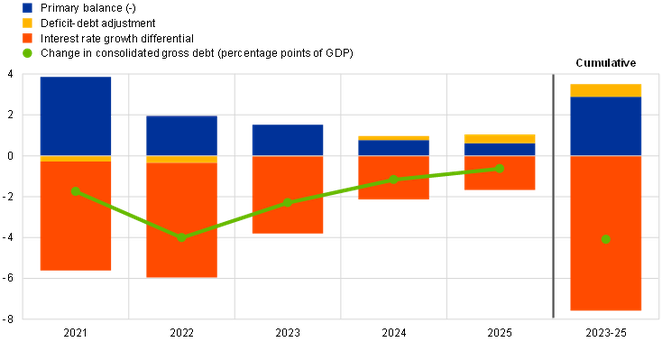

The euro area fiscal outlook is set to improve over the projection horizon. After the significant decline in 2022, the euro area budget deficit is projected to continue to decline at a slower pace over 2023-24 and only marginally in 2025 (to 2.5% of GDP). The decline in the budget balance at the end of the projection horizon, compared with 2022, is explained by the improvement in the cyclically adjusted primary balance and, to a more limited extent, by a better cyclical fiscal component, while interest payments gradually increase as a share of GDP over the horizon. Euro area debt is projected to continue to decline, albeit more slowly after 2022, to stand at 87.3% of GDP by 2025. This is mainly on account of negative interest rate-growth differentials, which more than offset the persisting primary deficits. Nevertheless, in 2025 both the deficit and debt ratios are expected to remain above pre-pandemic levels. Compared with the March 2023 projections, the budget balance remains broadly unchanged at the end of the horizon, while the debt ratio has been revised up somewhat over 2023-25 mainly on account of less favourable interest rate-growth differentials.

As the energy crisis fades, governments should roll back the related support measures promptly and in a concerted manner to avoid driving up medium-term inflationary pressures, which would call for a stronger monetary policy response. Fiscal policies should be designed to make the euro area economy more productive and gradually bring down high public debt. Policies to enhance the euro area’s supply capacity, especially in the energy sector, can also help reduce price pressures in the medium term. The reform of the EU’s economic governance framework should be concluded soon.

Inflation

Inflation fell further to 6.1% in May, according to Eurostat’s flash estimate, from 7.0% in April. The decline was broad-based. Energy price inflation, which had risen in April, resumed its downward trend and was negative in May. Food price inflation fell again but remained high at 12.5%.

Inflation excluding energy and food declined in May for the second month in a row, to 5.3% from 5.6% in April. Goods inflation decreased further, to 5.8% from 6.2% in April. Services inflation fell for the first time in several months, from 5.2% to 5.0%. Indicators of underlying price pressures remain strong, although some show tentative signs of softening.

Past increases in energy costs are still pushing up prices across the economy. Pent-up demand from the reopening of the economy also continues to drive up inflation, especially in services. Wage pressures, while partly reflecting one-off payments, are becoming an increasingly important source of inflation. Compensation per employee rose by 5.2% in the first quarter of the year and negotiated wages by 4.3%. Moreover, firms in some sectors have been able to keep profits relatively high, especially where demand has outstripped supply. Although most measures of longer-term inflation expectations currently stand at around 2%, some indicators remain elevated and need to be monitored closely.

According to the June 2023 projections, with energy inflation set to become increasingly negative throughout 2023 and food inflation moderating sharply, headline inflation is expected to continue its decline to stand at around 3% in the last quarter of the year. Nevertheless, HICP inflation excluding energy and food is projected to overtake headline inflation in the near term and to remain above it until early 2024, albeit following a gradual downward path from the second half of 2023. As indirect effects from the past energy price shocks and other pipeline price pressures gradually fade, driving the expected decline, labour costs will become the dominant driver of HICP inflation excluding energy and food. Wage growth is expected to remain over double its historical average for most of the projection horizon, driven by inflation compensation and the tight labour market, as well as increases in minimum wages. Nevertheless, profit margins, which expanded notably in 2022, are expected to act as a buffer against some of the pass-through of these costs in the medium term. In addition, monetary policy should further dampen underlying inflation in the coming years. Overall, headline inflation is expected to decrease from 8.4% in 2022 to an average of 5.4% in 2023, 3.0% in 2024 and 2.2% in 2025. Compared with the March 2023 projections, headline inflation has been revised up slightly over the entire projection horizon. This is mainly due to a significant upward revision to HICP inflation excluding energy and food, reflecting revisions owing to higher than expected recent inflation outcomes and somewhat stronger unit labour costs, which more than offset the effect of the lower energy price assumptions and tighter financing conditions.

Risk assessment

The Governing Council judges that the outlook for economic growth and inflation remains highly uncertain. Downside risks to growth include Russia’s unjustified war against Ukraine and an increase in broader geopolitical tensions, which could fragment global trade and thus weigh on the euro area economy. Growth could also be slower if the effects of monetary policy are more forceful than projected. Renewed financial market tensions could lead to even tighter financing conditions than anticipated and weaken confidence. Also, weaker growth in the world economy could further dampen economic activity in the euro area. However, growth could be higher than projected if the strong labour market and receding uncertainty mean that people and businesses become more confident and spend more.

Upside risks to inflation include potential renewed upward pressures on the costs of energy and food, also related to Russia’s war against Ukraine. A lasting rise in inflation expectations above the Governing Council’s target, or higher than anticipated increases in wages or profit margins, could also drive inflation higher, including over the medium term. Recent wage agreements in a number of countries have added to the upside risks to inflation. By contrast, renewed financial market tensions could bring inflation down faster than projected. Weaker demand, for example due to a stronger transmission of monetary policy, would also lead to lower price pressures, especially over the medium term. Moreover, inflation would come down faster if declining energy prices and lower food price increases were to pass through to other goods and services more quickly than currently anticipated.

Financial and monetary conditions

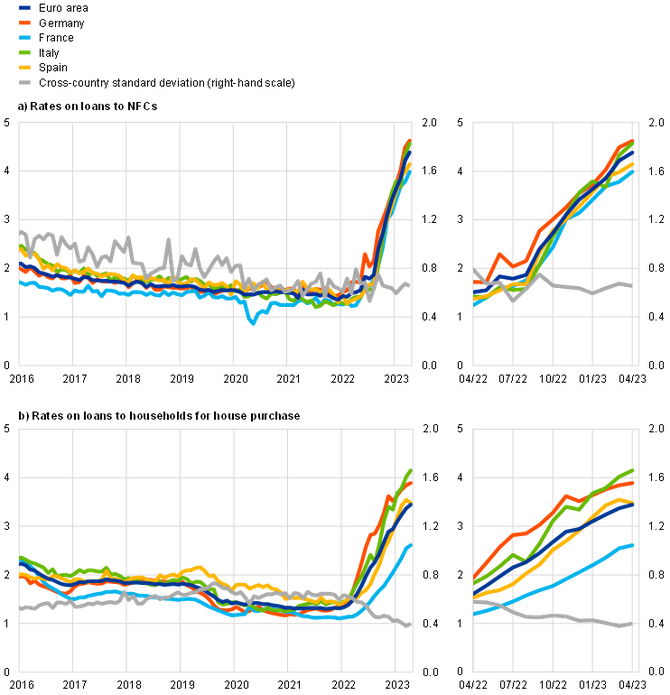

The monetary policy tightening continues to be reflected in risk-free interest rates and broader financing conditions. Funding conditions are tighter for banks and credit is becoming more expensive for firms and households. In April lending rates reached their highest level in more than a decade, standing at 4.4% for business loans and 3.4% for mortgages.

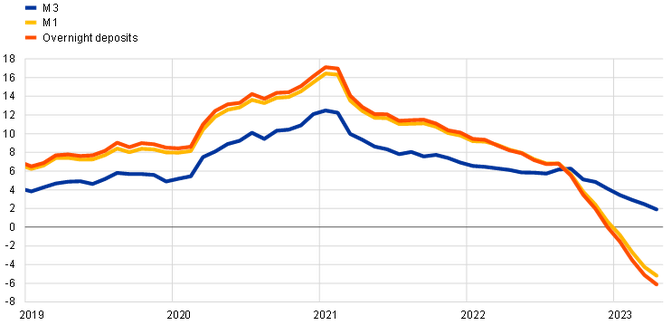

These higher borrowing rates, together with tighter credit supply conditions and lower loan demand, have further weakened credit dynamics. The annual growth of loans to firms declined again in April, to 4.6%. The month-on-month changes have been negative on average since November 2022. Loans to households grew at an annual rate of 2.5% in April and increased only marginally month on month. Weak bank lending and the reduction in the Eurosystem balance sheet led to a continued decline in annual broad money growth to 1.9% in April. Month-on-month changes in broad money have been negative since December.

In line with its monetary policy strategy, the Governing Council thoroughly assessed the links between monetary policy and financial stability. The financial stability outlook has remained challenging since the last review in December 2022. Tighter financing conditions are raising banks’ funding costs and the credit risk of outstanding loans. Together with the recent tensions in the US banking system, these factors could give rise to systemic stress and depress economic growth in the short term. Another factor weighing on the resilience of the financial sector is a downturn in the real estate markets, which could be amplified by higher borrowing costs and a rise in unemployment. At the same time, euro area banks have strong capital and liquidity positions, which mitigate these financial stability risks. Macroprudential policy remains the first line of defence against the build-up of financial vulnerabilities.

Monetary policy decisions

At its meeting on 15 June 2023, the Governing Council decided to raise the three key ECB interest rates by 25 basis points. Accordingly, the interest rate on the main refinancing operations and the interest rates on the marginal lending facility and the deposit facility were increased to 4.00%, 4.25% and 3.50% respectively, with effect from 21 June 2023.

The APP portfolio is declining at a measured and predictable pace, as the Eurosystem does not reinvest all of the principal payments from maturing securities. The decline will amount to €15 billion per month on average until the end of June 2023. The Governing Council will discontinue the reinvestments under the APP as of July 2023.

As concerns the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP), the Governing Council intends to reinvest the principal payments from maturing securities purchased under the programme until at least the end of 2024. In any case, the future roll-off of the PEPP portfolio will be managed to avoid interference with the appropriate monetary policy stance.

The Governing Council will continue applying flexibility in reinvesting redemptions coming due in the PEPP portfolio, with a view to countering risks to the monetary policy transmission mechanism related to the pandemic.

As banks are repaying the amounts borrowed under the targeted longer-term refinancing operations, the Governing Council will regularly assess how targeted lending operations and their ongoing repayment are contributing to its monetary policy stance.

Conclusion

Inflation has been coming down but is projected to remain too high for too long. The Governing Council therefore decided at its meeting on 15 June 2023 to raise the three key ECB interest rates by 25 basis points, in view of its determination to ensure that inflation returns to its 2% medium-term target in a timely manner.

The Governing Council’s future decisions will ensure that the key ECB interest rates will be brought to levels sufficiently restrictive to achieve a timely return of inflation to its 2% medium-term target and will be kept at those levels for as long as necessary. The Governing Council will continue to follow a data-dependent approach to determining the appropriate level and duration of restriction. In particular, the interest rate decisions will continue to be based on the Governing Council’s assessment of the inflation outlook in light of the incoming economic and financial data, the dynamics of underlying inflation, and the strength of monetary policy transmission.

In any case, the Governing Council stands ready to adjust all of its instruments within its mandate to ensure that inflation returns to its medium-term target and to preserve the smooth functioning of monetary policy transmission.

1 External environment

The global economy started this year on a stronger footing than in the fourth quarter of 2022 thanks to the reopening of the Chinese economy and the resilience of labour markets in the United States. Global activity was mainly driven by the services sector, whereas manufacturing output remains relatively subdued. The fallout from the US banking sector woes in early March led to a brief period of acute stress in global financial markets. Since then, most asset prices have recovered the losses recorded during that period, while financial market participants also revised down their expectations for the future path of the Federal Reserve System’s monetary policy tightening. Nonetheless, lingering uncertainty is adding to global growth headwinds, including high inflation, tightening in global financial conditions and geopolitical tensions. Against this backdrop, the global growth and inflation outlook in the June 2023 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections remains broadly unchanged compared with the March 2023 ECB staff exercise. The small upward revision to global growth in 2023 is mainly related to the stronger than previously expected recovery in demand in China in the first quarter, which was partially offset by the adverse impact of tighter financial and credit conditions in the United States and other advanced economies. The inflation outlook has been revised slightly upwards for 2024 against the backdrop of tight labour markets and still high wage growth in advanced economies, while lower commodity prices explain a small downward revision to projected inflation for 2023.World trade is projected to grow at a much slower pace than real GDP this year, as the composition of global demand has become less trade-intensive. The outlook for world trade for 2023 was revised down, albeit largely on account of sizeable negative carry-over effects from the fourth quarter of 2022 and weak outturns in in major economies the first quarter.

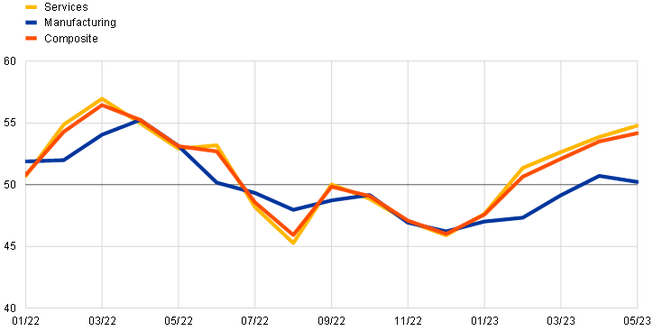

The global economy started this year on a stronger footing than in the fourth quarter of 2022 thanks to the reopening of China’s economy and the resilience of labour markets in the United States. Data coming from these countries have surprised on the upside since the beginning of the year. These surprises relate to an earlier and stronger than expected demand recovery in China, as pandemic-related disruptions proved short-lived. In the United States, the resilience of labour markets against the backdrop of significant tightening of monetary policy is underpinning consumer demand. Activity was mainly driven by the services sector, whereas manufacturing output remains relatively subdued (Chart 1). Global growth in the first quarter is estimated to have increased to 0.9%, from 0.5% in the previous quarter, and was 0.2 percentage points above the March projections.[1]

Chart 1

Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) output by sector across advanced and emerging market economies

a) Advanced economies (excluding the euro area)

(diffusion indices)

b) Emerging market economies

(diffusion indices)

Sources: S&P Global Market Intelligence and ECB staff calculations.

Note: The latest observations are for May 2023.

While acute financial stress in global financial markets triggered by the banking sector stress in the United States has receded, uncertainty remains high. The fallout from the US banking sector woes led to a short period of acute stress in global financial markets. Since then, most asset classes, with exception of financial stocks, have recovered the losses recorded during this period, while financial market participants also revised down their expectations for the future path of the Federal Reserve System’s monetary policy tightening. High uncertainty related to US banking sector developments is adding to global growth headwinds, including high inflation, tightening in financial conditions and elevated geopolitical uncertainty. Indeed, more recent data suggest that global growth has recently been losing momentum.

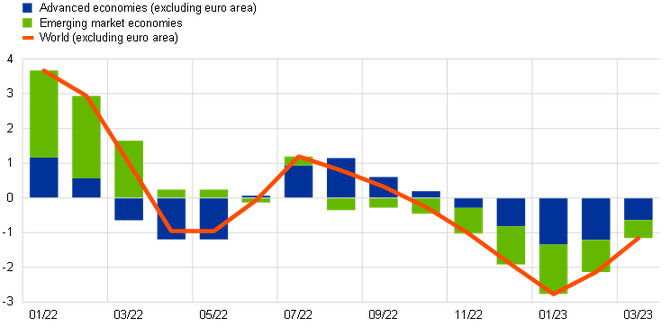

The global growth and inflation outlook remains broadly unchanged compared with the March 2023 staff projections. The world economy is projected to grow at 3.1% in both this year and next year, before accelerating slightly to 3.3% in 2025. Growth has been revised slightly upwards for 2023 (by 0.1 percentage points), slightly downwards for 2024 (by 0.1 percentage points) and remains unchanged for 2025. The stronger than previously expected recovery in demand in China in the first quarter of the year is a key factor explaining the upward revision of global growth in 2023, while the global growth outlook has been revised slightly down in the near term. The slightly slower than previously projected global growth in 2024 relates to the impact of tighter financial and credit conditions in the United States and other advanced economies.

As global activity is being predominantly driven by the services sector, which is less trade-intensive than the manufacturing sector, global trade remains weak. The decoupling between activity and trade can be explained by three compounding compositional effects, as activity is being driven by less trade-intensive geographies (emerging economies), demand components (consumption) and products (services). The negative compositional effects are expected to weigh on global trade over the near term, but their impact is expected to gradually dissipate thereafter. At the same time, the expected increase in demand for tradable services, such as tourism, which is continuing to rebound after the pandemic, the ongoing improvement of supply bottlenecks and the normalisation of the global inventory cycle should be supportive of global trade. Indeed, the latest data and estimates suggest that growth momentum in global goods trade has already become less negative and is expected to gradually improve going forward (Chart 2).

Chart 2

Merchandise trade momentum

(real imports, three-month-on-three-month percentage changes)

Sources: CPB and ECB staff calculations.

Note: The latest observations are for March 2023.

World trade is projected to grow at a much slower pace than real GDP this year as the composition of global demand has become less trade-intensive. World imports are projected to grow at 1.3% in 2023 – a very slow pace compared with its long-term average (4.8%) and also relative to global growth. Looking ahead, world trade is projected to increase by 3.4% in both 2024 and 2025. The implied trade elasticity – the ratio of global real import growth to global real GDP growth – over the projection horizon is close to unity. This is in line with the trade elasticity observed in the decade prior to the pandemic, but much lower than during the pandemic period. Euro area foreign demand is following a similar path, growing by 0.5% this year and picking up to 3.1% in both 2024 and 2025. Projections for both world trade and euro area foreign demand were revised down for this year, largely on account of sizeable negative carry-over effects from a weaker than previously estimated trade performance in the fourth quarter of 2022 and also due to weaker outturns in the first quarter of this year in major economies. For the rest of the projection horizon, trade projections are broadly in line with the March 2023 projections.

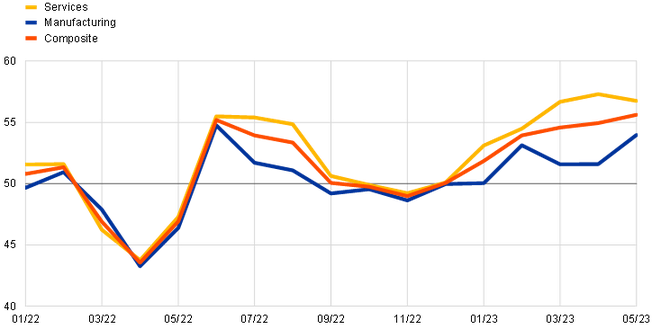

Underlying inflationary pressures in the global economy remain strong, while energy and food components continue to push down headline inflation. Headline consumer price index (CPI) inflation in the OECD area decreased to 7.4% in April from 7.7% in the previous month. While headline inflation is continuing to decline, thanks to lower energy and food price inflation, core inflation remained broadly stable at 7.1%, and its momentum, measured as three-month on three-month annualised percentage changes, has continued to edge up (Chart 3, red and orange bars). This suggests that underlying price pressures in the global economy remain strong. Even if tradable goods prices continue to normalise, thanks to easing of supply disruptions and falling shipping prices, inflation is likely to remain high owing to a more persistent services component, reflecting tight labour market conditions and high wage growth, especially in advanced economies. Growth in euro area competitor export prices (in national currencies) has been falling rapidly since the peak reached in the second quarter of 2022 on account of negative base effects for commodity prices and is expected to continue to do so in the near term, reflecting developments in the technical assumptions. Competitor prices are expected to grow at rates more in line with historical averages over the rest of the projection horizon, as the strong domestic and foreign pipeline pressures are expected to dissipate.

Chart 3

OECD headline inflation momentum

(three-month-on-three-month annualised percentage changes)

Sources: OECD and ECB calculations.

Notes: Contributions of respective components of OECD headline inflation momentum reported in the chart are constructed bottom-up using available country data, which jointly account for 84% of the OECD area aggregate. Goods inflation is computed as the residual of the contribution of total goods less those of energy and food. The latest observations are for April 2023.

Crude oil prices are lower than in the March projections as concerns about global growth outweighed the impact of the OPEC+ supply cut. Oil demand in OECD countries in the first quarter turned out to be weaker than the International Energy Agency (IEA) forecast at the beginning of the year. In addition, Russian oil production came in higher than expected. Although most of the Russian crude oil exports went to China, India and Türkiye, this helped to dampen the global price impact of stronger demand from China after its reopening. Furthermore, concerns about the global growth outlook against the backdrop of banking sector developments in the United States added to downward pressure on oil prices. European gas prices declined further to levels closer to the pre-pandemic average. On the back of continuously low consumption and successful substitution away from Russian gas, the European Union (EU) entered the replenishment season of its gas inventories with historically high storage levels of 55%. It also extended its gas savings plan until the end of March 2024, requiring Member States to reduce gas consumption by 15% relative to the 2017-2021 average. This implies that, even without gas imports from Russia, the EU appears to be safely on track to reach the 90% storage target ahead of the next heating season starting in November and that imports from other gas suppliers would not need to be as high as last year.

Global financial conditions tightened slightly across advanced and emerging market economies. While global risk sentiment has recently stabilised following a brief period of acute stress triggered by the Silicon Valley Bank failure in early March, uncertainty remains high. In the United States, the tightening of financial conditions since the March projections mainly reflects wider corporate spreads, while higher short-term yields also contributed somewhat. Overall, global financial markets appear cautiously optimistic, despite lingering uncertainty. At the same time, market expectations for US monetary policy tightening increased slightly, as the acute stress in the US banking sector receded, although they still remain below their levels in early March.

In the United States, real GDP is expected to decelerate in the first half of this year, followed by a tepid recovery. Household consumption growth is expected to remain positive thanks to a resilient labour market. A tightening of financial conditions has led to a decline in non-residential investment, which is now expected to last throughout 2023, while lingering uncertainty is expected to lead to an additional tightening of lending standards, further subtracting from growth. The agreement to suspend the US debt ceiling until January 2025 has alleviated financial market uncertainty. The agreement modestly cuts non-defence spending while leaving defence and mandated social security and health spending untouched. Headline CPI inflation stood at 4.9% in April, while core inflation, at 5.5%, remains high and persistent. Services are the main source of inflation persistence, owing to sticky prices for shelter services and the slow moderation of high wage growth. Moreover, goods inflation picked up again for the second consecutive month amid another sizeable increase in new vehicle prices and a smaller negative contribution from used vehicles and trucks.

The consumption-led recovery in China is continuing but appears to be losing steam. Following the rapid recovery of consumer spending after the reopening of the economy, the recovery momentum has been fading in the second quarter and the services and consumption-led recovery has not spilled over to manufacturing. The PMI for the services sector is pointing to strong growth, while the manufacturing sector PMI has declined slightly into contractionary territory. Retail sales in April increased strongly in annual terms, but this increase mainly reflects a low comparison base owing to widespread lockdowns in Shanghai last year. Growth momentum in retail sales decelerated and high-frequency data suggest that this trend continued in May. Following signs of a nascent recovery, housing market activity has taken a step back. In particular, housing investment declined significantly and housing sales, which had nearly stopped declining in year-on-year terms by March, contracted again. The continued weakness of the housing market remains a drag on the economy. Growth in house prices slowed in April, holding back consumer confidence. Annual headline CPI inflation slowed to 0.1% in April, the lowest reading in nearly two years, driven by sharp declines in the food and energy components. Core inflation (excluding food and energy) remained stable at 0.7%.

In Japan, economic activity is expected to continue to expand at a moderate pace, supported by pent-up demand and ongoing policy support. Real GDP grew in the first quarter of 2023, reflecting reopening dynamics, and is expected to continue to increase at a moderate pace. The services sector PMI rose further to very high levels in May, with companies citing waning coronavirus (COVID-19)-related disruptions and the resumption of domestic and foreign tourism as key factors behind the strong growth momentum in the sector, whereas manufacturing activity remains subdued. Inflation remained relatively high in April, and headline CPI inflation increased to 3.5%. Core CPI inflation (excluding food and energy) also continued to rise and stood at 2.5%. The latest indicators on the annual spring wage negotiations continue to point to significant wage increases relative to historical averages.

In the United Kingdom, the economy is set to avoid a recession in 2023, in spite of continuing growth headwinds. These relate to still high consumer price inflation weighing on disposable incomes, rising borrowing costs and the correction in the housing market. While the growth outlook in the near term is less adverse than previously expected, economic activity is expected to move sideways. Headline CPI inflation peaked in the fourth quarter of 2022 and was revised significantly downward for this year compared to the March 2023 projections owing to the extension of the energy price guarantee embedded in the Spring Budget. Nonetheless, headline inflation is expected to remain high as tight labour markets and strong wage pressures contribute to persistence in domestic inflation.

2 Economic activity

The euro area economy has stagnated in recent months. As in the fourth quarter of last year, it shrank by 0.1% in the first quarter of 2023 amid a drop in private and public consumption. Economic growth is likely to remain weak in the short run but strengthen in the course of the year as inflation comes down and supply disruptions continue to ease. Conditions in different sectors of the economy are uneven: manufacturing continues to weaken, partly owing to lower global demand and tighter euro area financing conditions, while services remain resilient. The labour market remains a source of strength. Almost a million new jobs were added in the first quarter of the year and the unemployment rate stood at a historical low of 6.5% in April. The average number of hours worked has also increased, although it is still somewhat below its pre-pandemic level.

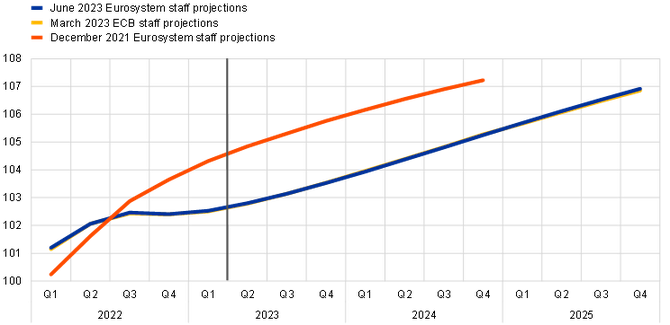

This outlook is broadly reflected in the June 2023 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, which foresee annual real GDP growth slowing down to 0.9% this year before rebounding to 1.5% in 2024 and to 1.6% in 2025. Compared with the March 2023 ECB staff macroeconomic projections, the outlook for growth is revised down by 0.1 percentage points in 2023 and 2024, while it remains unrevised for 2025. The outlook for economic growth remains highly uncertain.

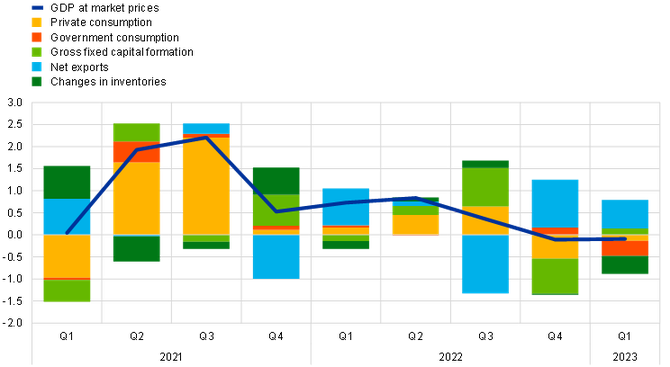

The euro area economy contracted slightly in the first quarter of 2023. According to revised Eurostat data, euro area real GDP declined by 0.1% in the first quarter of 2023, following an equal decline in the final quarter of 2022. This is despite real GDP being supported by lower energy prices, the easing of supply bottlenecks and fiscal policy. The expenditure breakdown shows positive contributions from net trade and investment (Chart 4). However, this was offset by negative contributions from private and public consumption and from changes in inventories. Quarter on quarter, GDP increased by 0.6% in Italy, 0.5% in Spain and 0.2% in France, while it declined by 0.3% in Germany and 0.7% in the Netherlands. The weak euro area outcome is also partly explained by a particularly strong decline in Irish GDP (-4.6%), which is again related to developments in the multinational-dominated sectors. Gross value added rose by 0.2% in the first quarter, reflecting a robust rise in output in construction as well as services, alongside a decline for value added in industry. The relatively large difference between GDP and value-added growth was due to a pronounced decline in net taxes on products, largely stemming from rising energy subsidies.

Chart 4

Euro area real GDP and its components

(quarter-on-quarter percentage changes; percentage point contributions)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Note: The latest observations are for the first quarter of 2023.

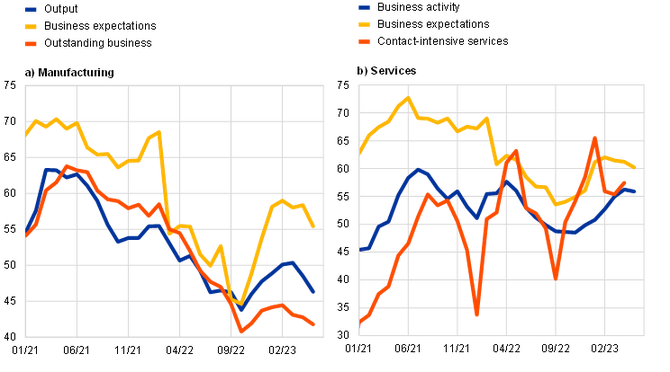

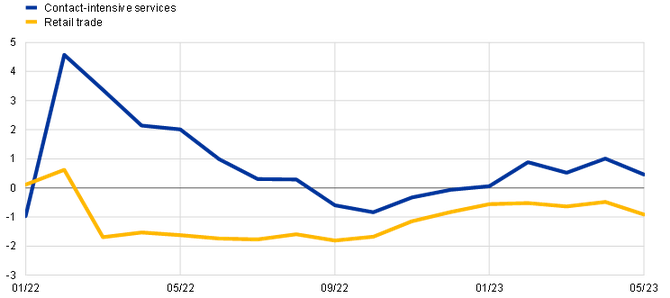

Euro area output is expected to display a moderate rise in the second quarter of 2023, mainly driven by the services sector. Incoming survey data suggest that the euro area economy may have modestly expanded in the second quarter of the year. The composite output Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) for the euro area stood at 52.8 in May, which is above its first quarter outcome and its long-term average. However, this growth signal masks a two-speed recovery. The manufacturing output index, which has declined for two consecutive months, stood at 46.4 in May, indicating that output may fall further (Chart 5, panel a). The latest PMI results also point to falling expectations with respect to future production and a falling backlog of orders. At the same time, the services business activity index stood at 55.1, up from 52.8 in the first quarter and indicative of a continued expansion (Chart 5, panel b). This improvement is partly explained by the rebound in demand for contact-intensive services after the easing of COVID-19-related restrictions. New orders are also rising in the sector, as are expectations for continued growth, albeit at a declining speed.

Chart 5

PMI indicators across sectors of the economy

(diffusion indices)

Source: S&P Global.

Note: The latest observations are for April 2023 for contact-intensive services and May 2023 for all other items.

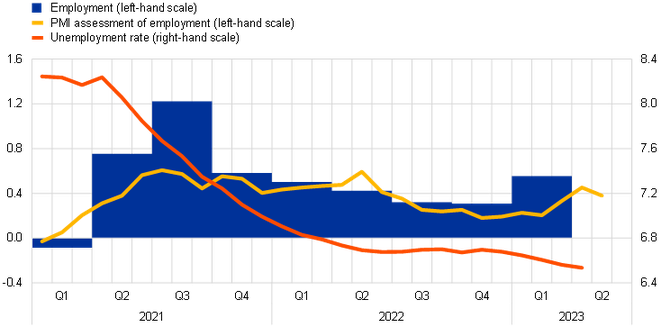

The labour market continued to expand in the first quarter of 2023 and remained resilient despite the decline in GDP. Employment and total hours worked increased by 0.6% in the first quarter of 2023. Since the fourth quarter of 2019 employment has increased by 2.9% and total hours worked has risen by 1.5% (Chart 6). This implies a 1.6% decline in average hours worked. This decline is partly related to strong employment creation in the public sector, which generally exhibits lower average hours worked compared with the total economy and elevated levels of sick leave. The labour force has continued to grow, remaining the main source of employment creation. Following very small increments of decline in recent quarters, the unemployment rate was at 6.5% in April, down by 0.2 percentage points since April 2022. Labour demand remains strong, with the job vacancy rate broadly stable at 3.0%, close to the highest level since the start of the series.

Chart 6

Euro area employment, the PMI assessment of employment and the unemployment rate

(left-hand scale: quarter-on-quarter percentage changes, diffusion index; right-hand scale: percentages of the labour force)

Sources: Eurostat, S&P Global Market Intelligence and ECB calculations.

Notes: The two lines indicate monthly developments, while the bars show quarterly data. The PMI is expressed in terms of the deviation from 50 divided by 10. The latest observations are for the first quarter of 2023 for employment, May 2023 for the PMI assessment of employment and April 2023 for the unemployment rate.

Short-term labour market indicators point to continued employment growth in the second quarter of 2023. The monthly composite PMI employment indicator declined from 54.5 in April to 53.8 in May, but remains significantly above the threshold of 50 that indicates an expansion in employment. This indicator has been in expansionary territory since February 2021, with a peak in May 2022. The overall deceleration suggests a moderation in employment growth. Looking at developments across different sectors, the indicator points to continued employment growth in the industry sector and especially the services sector, and to a slight decrease in the construction sector.

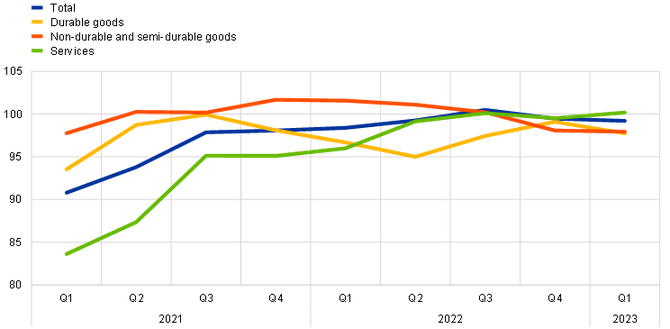

Private consumption contracted in the first quarter of 2023 amid a drop in spending on goods. Inflation remaining elevated and lingering uncertainty continued to dampen disposable income and encourage saving at the start of 2023. Against this background, private consumption contracted by 0.3% in the first quarter, driven by a decline in spending on goods (Chart 7, panel a). Quarter on quarter, retail sales fell by 0.2% in the first quarter of 2023 and stagnated in April 2023, while new passenger car registrations fell by 3.8% in the first three months of 2023, followed by a further monthly decline of 1.1% in April. In contrast, household consumption of services increased, still benefiting from lingering reopening effects.

Incoming data provide signs of a modest recovery in consumer spending. The European Commission’s consumer confidence indicator recovered in April, supported mainly by improving expectations about the general economic outlook and households’ own financial situations. However, it flattened in May, remaining at a low level. The outlook for consumer services remains stronger than that for goods, with the Commission’s indicator of expected demand for contact-intensive services remaining above its historical average level in April and May, despite a slight decline. In contrast, expected major purchases by consumers and expected retail trade business activity deteriorated in May and remained below historical averages (Chart 7, panel b). In a similar manner, the ECB’s Consumer Expectations Survey (CES) from April points to an increase in expected holiday bookings but no change in expected purchases of home appliances, the latter remaining at a low level and confirming an on-going dichotomy between the demand for services and the demand for goods. The transmission of tighter financing conditions to the real economy would likely curb household borrowing, increase savings and dampen consumer spending. The latest CES evidence suggests that an increasing share of households with an adjustable-rate mortgage expect to be late in repaying their debt.

Chart 7

Real private consumption indicators

a) Real private consumption components

(indices: fourth quarter of 2019 = 100)

b) Firms’ expectations about demand and business activity

(standardised percentage balances)

Sources: Eurostat, European Commission (Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs) and ECB calculations.

Notes: For panel b) expected demand for contact-intensive services in the next three months is standardised over the period 2005-19, while expected retail trade business situation in the next three months is standardised over the period 1985-2019. The latest observations are for the first quarter of 2023 for panel a) and for May 2023 for panel b).

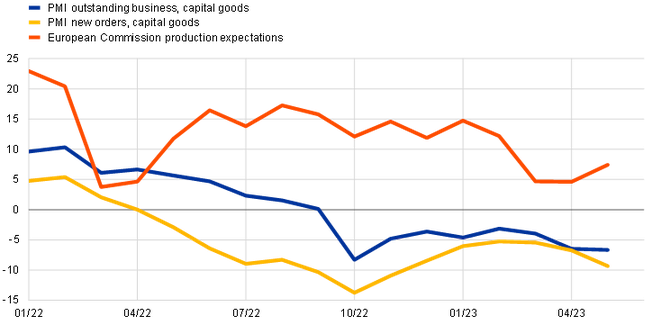

Business investment edged upward in early 2023, following a contraction in the fourth quarter of 2022. Quarter-on-quarter headline non-construction investment increased by 0.1% in the first quarter of 2023. This figure would, however, be higher if the volatile contribution from intangible investment in Ireland were excluded. Business investment is expected to have weakened in the current quarter. The production of capital goods declined strongly in March, implying a negative carry-over effect for the second quarter. Order books, manufacturing confidence, outstanding business and production expectations in the capital goods sector declined overall in the second quarter (Chart 8). A new index of corporate earnings sentiment based on earnings calls of large euro area companies shows that, despite experiencing a decline from the high values of the past years, corporate profits are still relatively robust.[2] This should mitigate the increasing effect of the rising cost of borrowing and tightening credit standards on corporate investment. The European Commission’s biannual investment survey, which was released on 27 April 2023, suggests an improvement in the balance of views (positive replies minus negative replies) compared with the October 2022 survey. The survey’s results imply positive growth in investment plans for 2023, both in the manufacturing sector and services sector. The highest balances are registered for service sectors such as telecommunications and infrastructure, which are characterised by longer-term investment needs related to digitalisation or the energy transition and are supported by the Next Generation EU programme. The survey also points to a broad-based expansion in both machinery and intangible investment that may still occur this year.

Chart 8

Short-term indicators for the capital goods sector

(deviations from averages)

Sources: Markit, European Commission and ECB calculations.

Notes: The PMI indicators are shown as deviations from the no-growth threshold of 50. The production expectations indicator of the European Commission is calculated as a deviation from its long-term average. The latest observations are for May 2023.

Housing investment increased in the first quarter of 2023 but is expected to contract again in the near term. Quarter on quarter, housing investment increased by 1.3% in the first quarter of 2023 following a 1.6% drop in the fourth quarter of 2022. This increase was likely due to favourable weather conditions, combined with companies’ healthy order backlog. The latter is reflected in the fact that the operating time required by the current backlog remained close to its historic high between January and April according to the European Commission’s quarterly survey. Building construction output increased significantly on average in the first quarter, but fell sharply in March, suggesting a weak starting point for the second quarter of 2023. Moreover, the Commission’s indicator of building construction activity over the past three months declined markedly on average in April and May compared with the first quarter average. In addition, the PMI for residential construction fell further into contractionary territory. As demand is dwindling, bottlenecks on the supply side, such as material shortages and longer delivery times, are decreasing significantly, with the number of residential real estate transactions having fallen by double-digit year-over-year rates in many countries in the fourth quarter of 2022. Sentiment, as measured by the Commission’s quarterly survey of households’ intentions to renovate, buy or build a house, improved slightly from January to April, but it is still depressed. The decline in demand is due to the rise in mortgage rates, which, together with lower real income and high house prices, affects affordability. This is also reflected in the significant decline in demand for housing loans.

Euro area export volumes growth continued to be subdued in the first quarter of the year due to weakening global demand. Extra-euro area goods exports fell moderately in the first quarter as global foreign demand weakened. Manufacturing exports were supported by easing supply bottlenecks, whereas lingering effects from the energy supply shock and the appreciation of the euro have contributed to export weakness. Exports of services bolstered total euro area exports. Euro area imports decreased sharply in the first quarter, reflecting a slowdown in domestic demand and lower energy imports amid a mild winter and filled stores. With import volumes contracting, net trade contributed positively to GDP growth in the first quarter despite subdued export growth. The euro area terms of trade continued to improve as energy import prices decreased further, which contributed to an expeditious return of the current account into surplus in the first quarter of 2023. Forward-looking indicators point to continued near-term weakness in euro area export volumes. Suppliers’ delivery times continued to shorten in May, and export performance should be supported in the short term by the drawdown of existing order books that are still elevated in some key industries. However, new manufacturing export orders fell back further into contractionary territory, indicating a continued sluggish demand for euro area goods exports. At the same time, the increase in new orders for services exports points to positive momentum in that sector, with strong activity in travel and transport as well as other tradable services, such as information and communication technology.

Beyond the near term, GDP growth is expected to gradually strengthen. The economy is expected to return to growth in the coming quarters as energy prices moderate, foreign demand strengthens, supply bottlenecks are resolved and uncertainty – including that related to the recent banking sector stress – continues to recede. Furthermore, real incomes are set to improve, underpinned by a robust labour market and unemployment hitting new historical lows. Although the ECB’s monetary policy tightening will increasingly feed through to the real economy, the dampening effects from tighter credit supply conditions are expected to be limited. Together with the gradual withdrawal of fiscal support, this will weigh on economic growth in the medium term.

The June 2023 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area foresee annual real GDP growth slowing down to 0.9% in 2023 (from 3.5% in 2022), before rebounding to 1.5% in 2024 and 1.6% in 2025 (Chart 9). Compared with the March 2023 ECB staff projections, the outlook for GDP growth has been revised down by 0.1 percentage points for 2023 and 2024, primarily reflecting tighter financing conditions. Projected GDP growth in 2025 remains unchanged, as the effects of tighter financing conditions are expected to be partly offset by the effects of higher real disposable income and lower uncertainty.

Chart 9

Euro area real GDP (including projections)

(index: fourth quarter of 2019 = 100; seasonally and working day-adjusted quarterly data)

Sources: Eurostat and the June 2023 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area.

Note: The vertical line indicates the start of the June 2023 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections.

3 Prices and costs

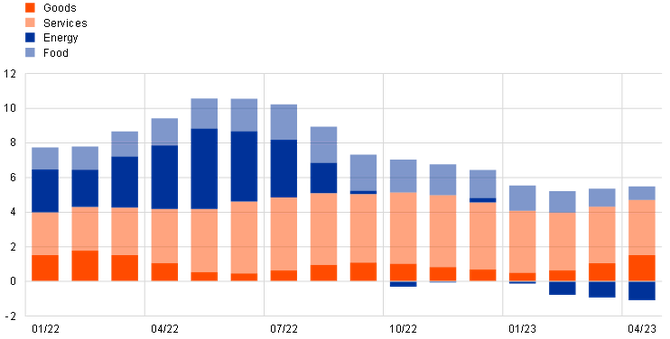

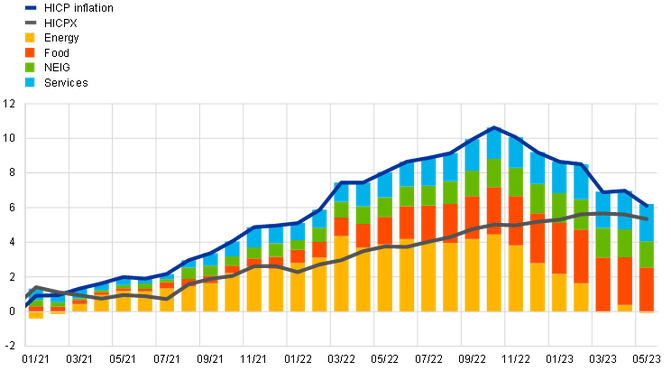

According to Eurostat’s flash estimate, inflation was 6.1% in May 2023, resuming its downward path which started in October 2022.All the main subcomponents – energy, food, non-energy industrial goods (NEIG) and services – contributed to the decline in headline inflation. Price pressures remained strong, but some showed tentative signs of easing, with the effects of high energy costs, supply bottlenecks and the reopening of the economy slowly fading out. Wage pressures have become an increasingly important source of inflation, while profits remained relatively high in sectors with supply-demand imbalances. The latest available data for indicators of underlying inflation showed tentative signs of levelling off, but they still stand at elevated levels. Although most measures of longer-term inflation expectations continued to stand at around 2%, some indicators remained elevated and warrant continued monitoring. The June 2023 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections foresee headline inflation continuing its downward path, averaging 5.4% in 2023, 3.0% in 2024 and 2.2% in 2025.

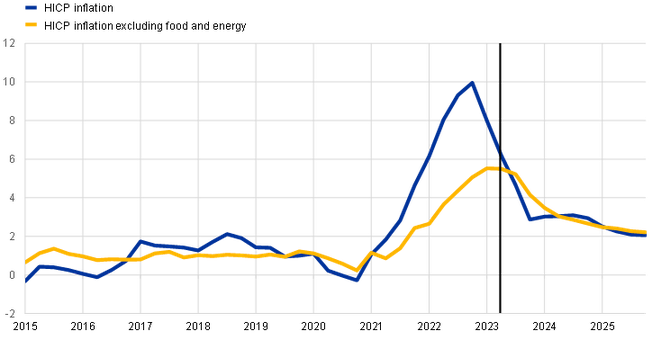

According to Eurostat’s flash estimate, HICP inflation declined to 6.1% in May, resuming its earlier unwinding after the small uptick to 7.0% in April, which reflected an upward base effect in energy inflation (Chart 10). The decline in May was driven by lower inflation rates across all the main HICP subcomponents (energy, food, NEIG and services). Energy inflation decreased to -1.7% in May, thus resuming its downward trend after rising to 2.4% in April from -0.9% in March. The overall decrease in energy inflation over recent months has been linked to falling wholesale gas and electricity prices. Food inflation declined further, falling from 13.5% in April to 12.5% in May, as a result of lower rates for both unprocessed and processed food components. This is in line with moderating pipeline price pressures, as the indirect effects of energy and other cost shocks unwind. HICP inflation excluding energy and food (HICPX) stood at 5.3%, down from 5.6% in April, thus showing a decrease for the second consecutive month. This decrease stemmed from lower inflation rates for both services and NEIG. The latter declined further to 5.8% in May, compared with 6.2% in April, likely reflecting to a large extent the easing of the past upward pressures from supply bottlenecks and energy cost shocks. This decrease potentially also reflects a post-pandemic rotation in demand from goods to services. Services inflation also decreased slightly from 5.2% in April to 5.0% in May.

Chart 10

Headline inflation and its main components

(annual percentage changes; percentage point contributions)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Note: The latest observations are for May 2023 (flash estimates).

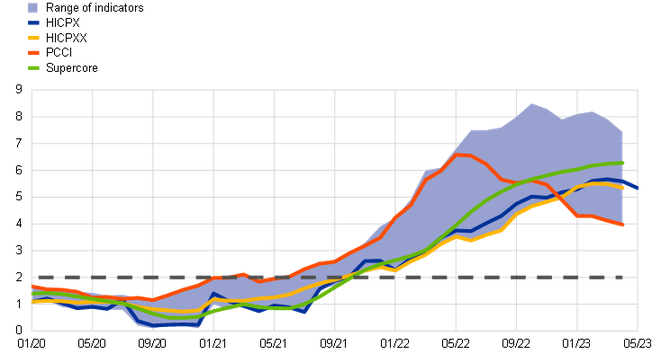

Most indicators of underlying inflation in the euro area show tentative signs of levelling off, although they still stand at elevated levels and uncertainty remains high (Chart 11). According to the latest available data, most indicators of underlying inflation displayed a small decline in their annual growth rates in April. Moreover, HICPX inflation saw a further decline to 5.3% in May (flash release), supporting the expectation of an emerging downward path for core inflation. Compared with the previous month, the only underlying inflation indicators which still rose in April were the Supercore indicator (which comprises HICP items sensitive to the business cycle) and the domestic inflation indicator (which excludes items with a high import content). This points to the prevalence of some more persistent domestic price pressures. Together with some lagged pass-through of previous shocks in energy costs and supply chains, underlying inflation rates have thus remained elevated. The range of monitored indicators narrowed in April but remained wide by historical standards, signalling that heightened uncertainty remains.

Chart 11

Indicators of underlying inflation

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Notes: The range of indicators of underlying inflation includes HICP excluding energy, HICP excluding energy and unprocessed food, HICPX, HICPXX, 10% and 30% trimmed means, PCCI and a weighted median. The grey dashed line represents the ECB’s inflation target of 2% over the medium term. The latest observations relate to May 2023 (flash estimate) for HICPX and to April 2023 for the other indicators.

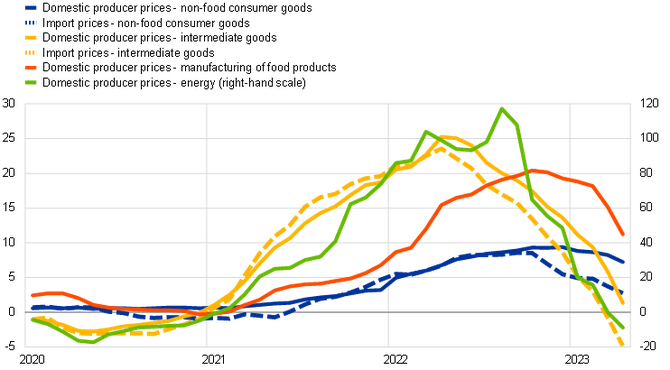

Pipeline pressures continued to ease but some indicators remain at historically high rates, especially at the later stages of the pricing chain (Chart 12). At the early stages of the pricing chain, price pressures continued to decrease substantially in April, with domestic producer price inflation for intermediate goods declining to 1.3% from 5.8% in March. The annual growth rate of import prices for intermediate goods became more negative, falling from -0.8% in March to -4.8% in April, owing in part to the appreciation of the euro exchange rate in autumn 2022. The waning impact of the energy price shocks was also reflected in producer price inflation for energy, which entered negative territory in April. Looking at the later stages of the pricing chain, domestic producer price inflation for non-food consumer goods edged down further, from 8.2% in March to 7.2% in April. However, it continues to stand at remarkably high levels. Over the same period, the annual growth rate in import prices for non-food consumer goods declined to 2.8% from 3.7%. The continued easing of pipeline pressures suggests that the cumulative effect of past price shocks is fading. The annual growth rate in producer prices for food products also declined, with domestic producer price inflation at 11.2% in April and the equivalent series for import prices at 3.5%.

Chart 12

Indicators of pipeline pressures

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Note: The latest observations are for April 2023.

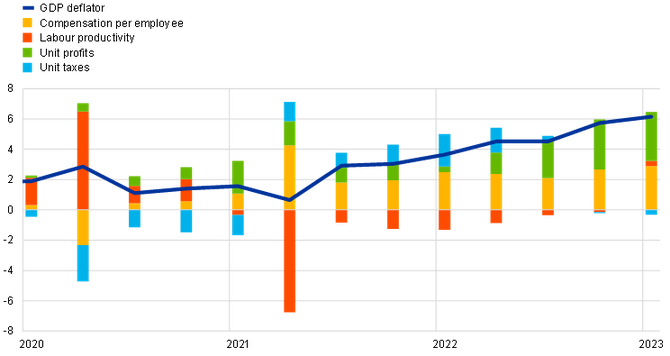

Domestic cost pressures, as measured by the GDP deflator, continued to increase in the first quarter of 2023 as a result of rising unit labour costs and unit profits (Chart 13). The year-on-year growth rate of the GDP deflator increased to 6.2% in the first quarter of 2023, compared with 5.8% in the fourth quarter of 2022, thus surpassing HICPX inflation. Unit profits and unit labour costs each contributed to around half of the total growth rate of the GDP deflator, whereas unit taxes had a minor downward impact. The contribution of unit profits to the GDP deflator remained high from a historical perspective.[3] This implies that the supply-demand imbalances in some sectors have not fully faded yet and that firms have benefited from a favourable pricing environment in which increases in input prices could be passed through to selling prices. The increase in unit labour costs growth stemmed mainly from a decline in labour productivity, which fell from 0.3% in the final quarter of 2022 to -0.6% in the first quarter of 2023. There was also a positive contribution from the increase in compensation per employee growth, which rose from 4.8% to 5.2% over the same period. A strengthening in wage pressures is also observed in the growth rate of negotiated wages, which increased by 4.3% in the first quarter of 2023, compared with 3.1% in the previous quarter. Moreover, forward-looking information from recently concluded wage negotiations suggests that nominal wage pressures remain strong, especially when also considering the one-off payments which were prevalent in recent agreements in some euro area countries.

Chart 13

Breakdown of the GDP deflator

(annual percentage changes; percentage point contributions)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Notes: The latest observations are for the first quarter of 2023. Compensation per employee and labour productivity both contribute to changes in unit labour costs.

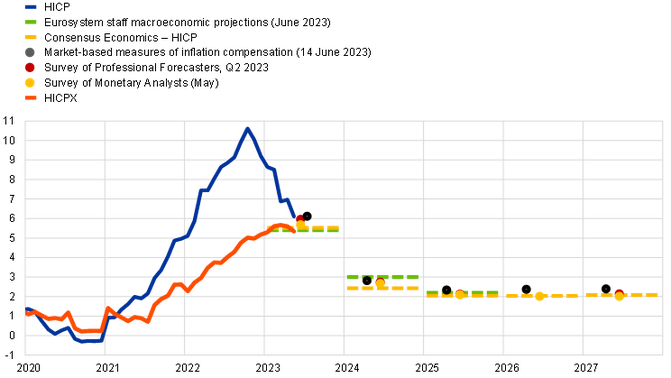

Most survey-based indicators of longer-term inflation expectations in the euro area remain at around 2%, while market-based measures of inflation compensation have slightly increased. Survey-based indicators of longer-term inflation expectations by professional forecasters continue to stand at around the ECB’s 2% target. In the ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters for the second quarter of 2023, average longer-term inflation expectations (which relate to 2027) were unchanged at 2.1%, while the ECB Survey of Monetary Analysts for May 2023 gave longer-term expectations of 2.0%, unchanged from the March release. Market-based measures of inflation compensation (based on HICP excluding tobacco) increased slightly across all maturities over the review period, which ended in mid-June, amid market participants’ increased focus on whether there is evidence for the persistence of core inflation in the euro area and elsewhere. Lower than expected data for euro area core and headline inflation released at the end of May did not materially change this pricing in forward markets. At the short end, the one-year forward inflation-linked swap rate one year ahead stood at 2.3% in mid-June, 15 basis points higher than at the beginning of the review period in mid-March. At the long end, the five-year forward inflation-linked swap rate five years ahead also ended the review period almost 15 basis points higher and is hovering at 2.5%. However, it should be noted that market-based measures of inflation compensation are not a direct gauge of market participants’ genuine inflation expectations, given that these measures also include inflation risk premia which compensate for inflation risks. On the consumer side, the latest ECB Consumer Expectations Survey (April 2023) reports that median expectations for headline inflation three years ahead decreased significantly to 2.5% from 2.9%, while median one-year ahead expectations declined to 4.1% from 5.0%.[4] As a result, the increase in three-year inflation expectations observed in March has been broadly reversed, indicating that this temporary uptick could be attributed to uncertainties and concerns about financial market turmoil in Europe.

Chart 14

Survey-based indicators of inflation expectations and market-based measures of inflation compensation

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: Eurostat, Refinitiv, Consensus Economics, Survey of Professional Forecasters, Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, June 2023, and ECB calculations.

Notes: The market-based measures of inflation compensation series is based on the one-year spot inflation rate, the one-year forward rate one year ahead, the one-year forward rate two years ahead and the one-year forward rate three years ahead. The observations for market-based measures of inflation compensation relate to 14 June 2023. The ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters for the second quarter of 2023 was conducted between 31 March and 5 April 2023. The cut-off date for the Consensus Economics long-term forecasts was April 2023, and May 2023 for the near-term forecasts (2023 and 2024). The cut-off date for data included in the Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections was 31 May 2023. The latest observation for HICP relates to May 2023 (flash estimate).

The June 2023 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections envisage headline inflation continuing its downward path, averaging 5.4% in 2023, 3.0% in 2024 and 2.2% in 2025 (Chart 15). Headline inflation has come down since October last year, although it is proving more persistent than previously anticipated, despite initial signs of easing underlying price pressures. Energy inflation is expected to become increasingly negative in 2023 as energy commodity prices continue to decline, and food inflation is expected to moderate. Together with easing supply bottlenecks, these factors are expected to drive headline inflation further down to 3.0% in the last quarter of 2023. Inflation is expected to hover around this level in 2024 when fiscal measures are expected to unwind, before gradually falling further in 2025. HICPX will gradually moderate in the course of 2023, averaging 5.1% in 2023, 3.0% in 2024 and 2.3% in 2025. The receding impact of pipeline pressures is expected to outweigh a strengthening of labour cost pressure, as wage growth remains above historical averages as a result of compensation for the loss in purchasing power and tight labour markets. A contraction of unit profits is expected to somewhat buffer stronger labour cost dynamics. Over the course of the projections horizon, the fading of the indirect effects of energy prices, easing supply bottlenecks and the dampening impact of monetary policy should all contribute to bringing inflation down. Compared with the March 2023 staff projections, the profile of headline inflation has remained broadly the same, with an upward revision of 0.1 percentage point in each year. HICPX has been revised up, owing to past upward surprises and pressure from unit labour costs growth.

Chart 15

Euro area HICP and HICPX inflation

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: Eurostat and Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area (June 2023).

Notes: HICP stands for Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices. HICPX stands for HICP inflation excluding energy and food. The vertical line indicates the start of the projection horizon. The latest observations are for the first quarter of 2023 for the data and the fourth quarter of 2025 for the projections. The June 2023 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area were finalised at the end of May and the cut-off date for the technical assumptions was 23 May 2023. Historical data for HICP and HICPX inflation are at quarterly frequency. Forecast data are at quarterly frequency for HICP inflation and annual frequency for HICPX inflation.

4 Financial market developments

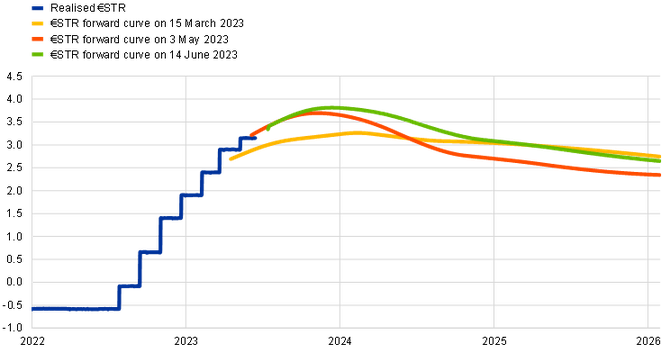

During the review period (16 March to 14 June 2023) financial markets in the euro area stabilised following the banking sector turmoil that had been triggered in the United States in early March. As concerns about the economic impact of the turmoil gradually abated, market participants reappraised their expectations regarding higher policy rates, volatility receded, equities recovered and corporate bond spreads narrowed. At the end of May risk-free rates declined slightly across all maturities, partly owing to lower than expected core and headline inflation in the euro area. Overall, the euro short-term rate (€STR) forward curve rose at the very short end, peaking at around 3.8% by the end of the review period in mid-June – although this level was still lower than in early March before the onset of the banking turmoil. Euro area long-term risk-free rates only partially mirrored the increases in their US and UK counterparts and stabilised slightly higher than in mid-March. Sovereign bond markets were broadly insulated from events in the banking sector, and spreads did not react to the Governing Council’s announcement that it expected to discontinue reinvestments under the asset purchase programme (APP) as of July 2023. Euro area aggregate equity price indices increased to a lesser extent than in the United States over the review period, while the euro area banking sector outperformed its US counterpart. Spillovers to the euro area from financial market volatility in the United States related to the political uncertainty about the US debt ceiling were largely contained. Finally, in foreign exchange markets, the euro appreciated in trade-weighted terms.

The overnight index swap (OIS) forward curve rose at the very short end and the €STR forward curve peaked at around 3.8% (Chart 16). The benchmark €STR closely followed the changes in the deposit facility rate, which the Governing Council raised by 50 basis points (from 2.5% to 3%) at its monetary policy meeting on 16 March 2023 and by an additional 25 basis points (from 3% to 3.25%) at its meeting on 4 May. At the beginning of March the OIS forward curve, based on the €STR, was pricing in a peak rate of 4% by December 2023, which then declined to 3.3% by October 2023, on the back of market participants’ growing concerns about the banking sector turmoil. In the second half of March the Governing Council’s decision to increase the deposit facility rate, coupled with the reinforcement of the data-dependent approach to policy rate setting and clear communication about the resilience of the euro area banking sector, led market participants to revise their monetary policy expectations upwards. The Governing Council’s decision in May did not have a significant impact on the policy rate path that market participants had priced in the OIS forward curve. However, lower than expected data releases for euro area core and headline inflation at the end of May slightly dampened policy rate expectations. Over the review period as a whole the OIS forward curve rose at the very short end and priced in a peak rate of 3.8% for October 2023. Compared with the OIS forward curve prevailing before the Governing Council’s May meeting, the mid-June forward curve shows a similar peak, but a more moderate decline in forward rates thereafter.

Chart 16

€STR forward rates

(percentages per annum)

Sources: Thomson Reuters and ECB calculations.

Note: The forward curve is estimated using spot OIS (€STR) rates.

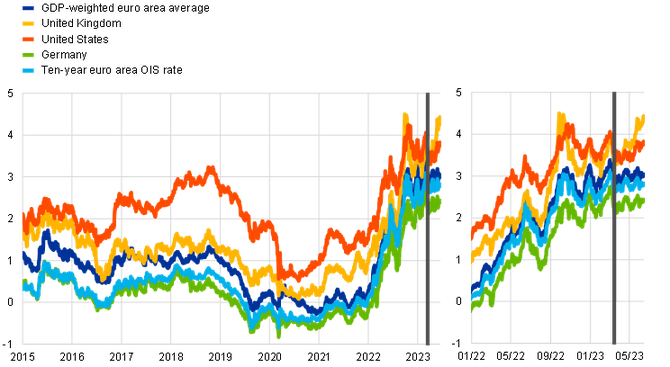

Euro area long-term risk-free rates only partially mirrored the increases in their US and UK counterparts and stabilised slightly higher than at the beginning of the review period in mid-March (Chart 17). Long-term risk-free rates in the euro area declined notably at the start of the review period as financial market participants reappraised their policy rate expectations in the aftermath of the banking turmoil. The ten-year GDP-weighted euro area sovereign bond yield stood at 3% in mid-March. From there, it fluctuated in a range of around 40 basis points, ending the review period in mid-June 10 basis points higher, at 3.1%, in particular contrast to the marked rise in UK long-term risk-free rates. The debate surrounding the US debt ceiling, on which an agreement was passed by the House of Representatives on 31 May, together with improved risk sentiment and the Bank of England’s ongoing tightening stance, were the main drivers of the stronger increase in US and UK ten-year government bond yields, which rose by 20 basis points and 100 basis points respectively, to reach 3.8% and 4.4% in mid-June.

Chart 17

Ten-year sovereign bond yields and the ten-year OIS rate based on the €STR

(percentages per annum)

Sources: Refinitiv and ECB calculations.

Notes: The vertical grey line denotes the start of the review period on 16 March 2023. The latest observations are for 14 June 2023.

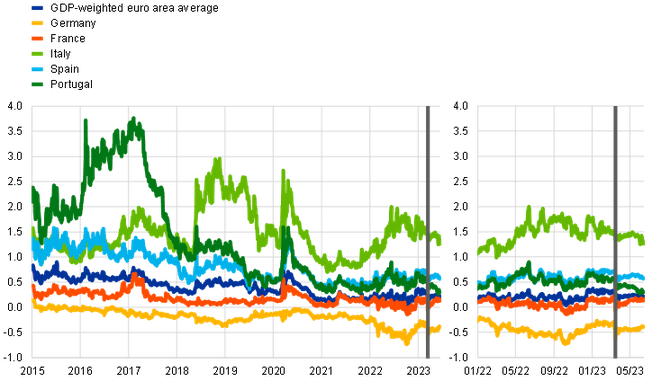

Euro area sovereign bond yields moved broadly in line with developments in risk-free rates as sovereign spreads remained insulated from concerns over the banking sector, rating actions and the Governing Council’s APP decisions (Chart 18). The GDP-weighted euro area average sovereign bond spread over the OIS rate based on the €STR increased only slightly over the review period, echoing sovereign bond spreads, which remained broadly stable, in most jurisdictions. The main driver of the upward movement was the German ten-year sovereign bond spread, which increased by 12 basis points to become less negative, in part reflecting a reversal of the flight-to-safety flows sparked by the banking sector turmoil. The Governing Council’s announcement in May that it expected to discontinue reinvestments under the APP as of July 2023 did not prompt any visible widening of spreads. The most notable movement during the review period was the decline in the Greek sovereign bond spread following the first round of parliamentary elections on 21 May, which strengthened market participants’ expectations of a possible upgrade to investment-grade status in the coming months. The Greek ten-year sovereign bond spread fell by 60 basis points over the review period as a whole.

Chart 18

Ten-year euro area sovereign bond spreads vis-a-vis the ten-year OIS rate based on the €STR

(percentage points)

Sources: Refinitiv and ECB calculations.

Notes: The vertical grey line denotes the start of the review period on 16 March 2023. The latest observations are for 14 June 2023.

Corporate bond spreads narrowed over the review period on the back of improved risk sentiment. Spreads on high-yield and investment-grade corporate bonds narrowed by 77 basis points and 13 basis points respectively, almost correcting the widening that had occurred during the banking sector turmoil preceding the review period. While spreads were marginally higher than they were prior to the banking turmoil, gross issuance by non-financial corporations (NFCs) was in line with historical regularities. Gross issuance was stronger at the start of 2023 than the average gross issuance over the last ten years, but it almost came to a halt when the banking sector turmoil started and spreads widened significantly, only to pick up again when spreads started to narrow and volatility diminished. The ability of NFCs to adapt to the prevailing market conditions and issue less debt when corporate bond spreads moved higher may have prevented spreads from widening further during the turmoil.

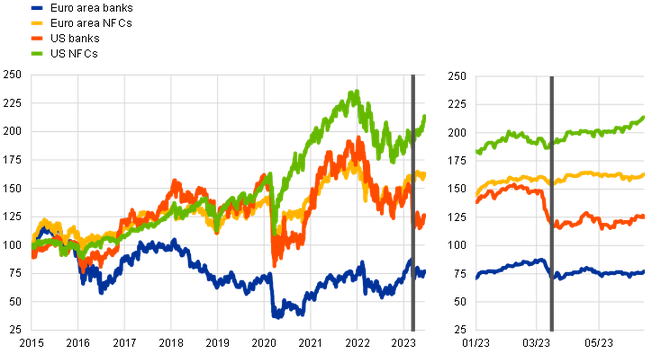

Euro area equity prices increased over the review period as stock markets settled into an environment of lower volatility (Chart 19). Over the review period euro area stock market indices saw a broad-based increase of 5%, largely making up the losses suffered during the banking sector turmoil, although bank equity prices have not yet fully recovered the loss. As the US debt ceiling deadline approached, equity markets on both sides of the Atlantic were relatively calm. Notwithstanding the more persistent drag on the equity prices of US banks, aggregate equity indices fared better in the United States than in the euro area, boosted by the general outperformance of NFCs – especially in the technological sector – which carry a relatively higher weight in US indices than in the euro area. In the euro area, NFC equity prices increased by 4.5%, driven by higher than expected dividends and share buybacks, as well as higher short-term earnings expectations, which were partially offset by a deterioration in the longer-term outlook for earnings, and in the United States they rose by 11% over the review period as a whole. Bank equity prices gained 5.7% in the euro area and 1.9% in the United States.

Chart 19

Euro area and US equity price indices

Sources: Refinitiv and ECB calculations.

Notes: The vertical grey line denotes the start of the review period on 16 March 2023. The latest observations are for 14 June 2023.

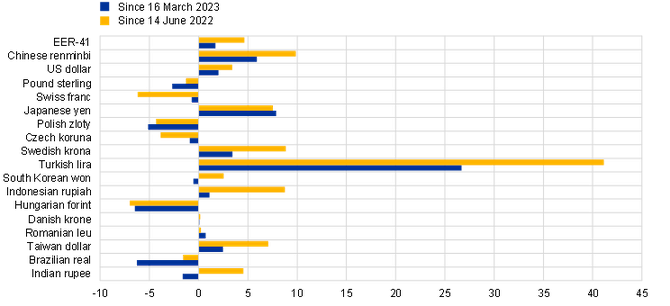

In foreign exchange markets, the euro appreciated in trade-weighted terms (Chart 20). During the review period the nominal effective exchange rate of the euro – as measured against the currencies of 41 of the euro area’s most important trading partners – appreciated by 1.7%. In terms of bilateral exchange rate movements against major currencies, the euro appreciated against the US dollar (by 2.0%), despite a widening of interest rate differentials, as well as against the Chinese renminbi (by 5.9%) and the Japanese yen (by 7.9%), while it depreciated against the pound sterling (by 2.7%) and the Swiss franc (by 0.7%). It also strengthened against the currencies of most major emerging economies in Asia, as well as against the Turkish lira (by 26.7%), but weakened against the Brazilian real (by 6.3%) and against the currencies of most central and eastern European non-euro area EU Member States.

Chart 20

Changes in the exchange rate of the euro vis-a-vis selected currencies

(percentage changes)

Source: ECB.

Notes: EER-41 is the nominal effective exchange rate of the euro against the currencies of 41 of the euro area’s most important trading partners. A positive (negative) change corresponds to an appreciation (depreciation) of the euro. All changes have been calculated using the foreign exchange rates prevailing on 14 June 2023.

5 Financing conditions and credit developments

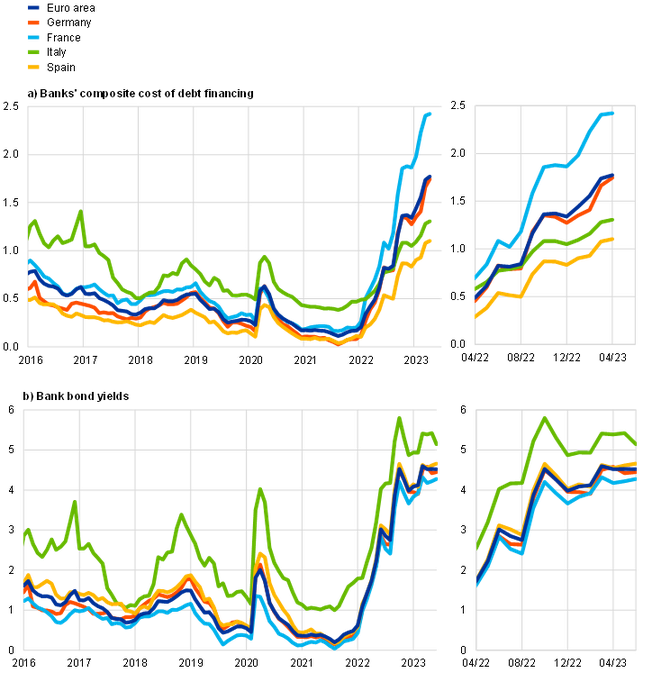

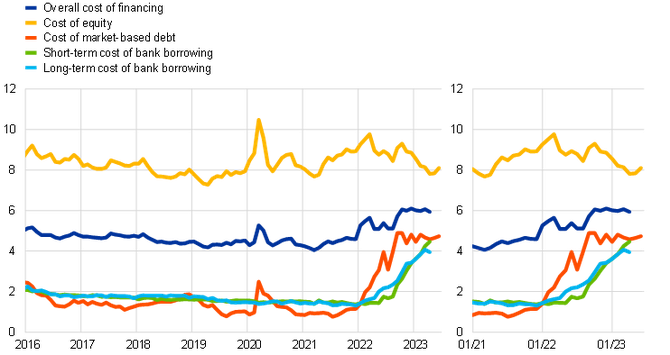

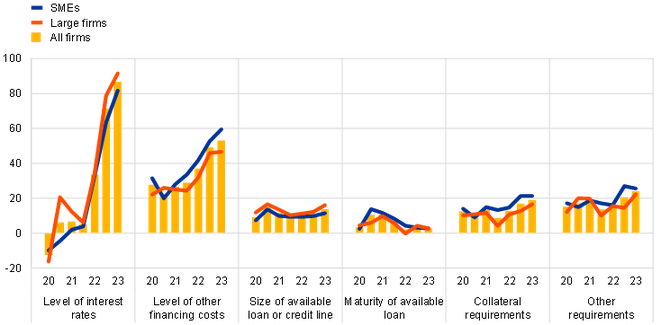

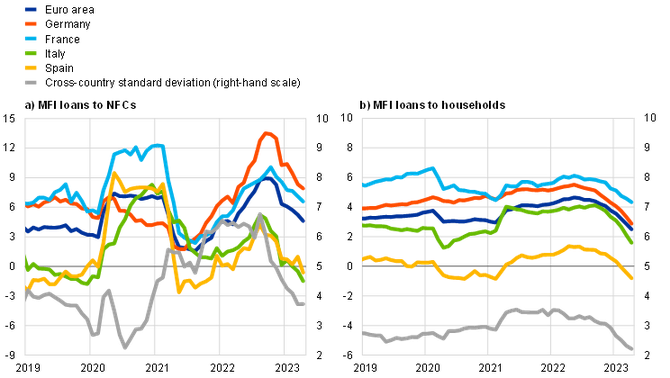

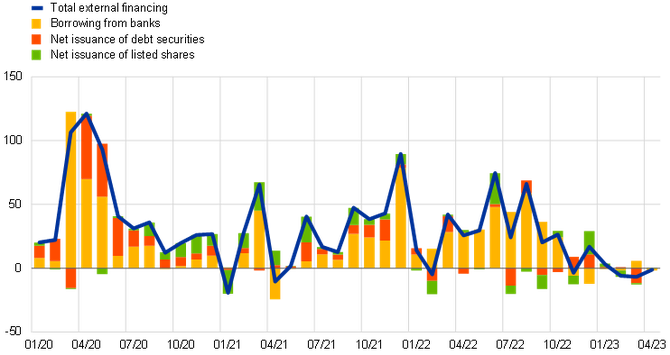

Bank funding costs continued to rise in April 2023, reflecting further increases in the key ECB interest rates. Bank lending rates also increased for firms and households, though at a slower pace than in previous months. Over the period from 16 March to 14 June 2023 the cost of both equity financing and market-based debt financing increased only marginally. Bank lending to firms and households continued to moderate in April, amid higher lending rates, lower loan demand and tighter credit standards. The weakening of monetary dynamics continued, driven by high opportunity costs of holding money, slowing credit dynamics and the reduction of the Eurosystem’s balance sheet.

Euro area bank funding costs continued to rise in April, reflecting further increases in the key ECB interest rates and deposit rates. The composite cost of debt financing for euro area banks increased slightly further in April, thus stabilising around its highest level for more than ten years (Chart 21, panel a). The recent increase mostly reflects higher deposit rates, while bank bond yields remained broadly stable (Chart 21, panel b). Deposit rates continued to rise steadily, with some variation across instruments. Depositors are reacting to the widening spread between time deposit rates and rates on overnight deposits by shifting their holdings from overnight to time deposits and to other instruments with higher remuneration. The pass-through of the increases in the key ECB interest rates to deposit rates has varied significantly across banks and has been accompanied by a redistribution of deposit volumes between banks. Savers have reallocated deposits from banks with less attractive remuneration towards banks that have increased deposit rates at a faster pace.

Bank repayments of funds borrowed under the third series of targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO III) contributed to a further reduction in excess liquidity and to higher bank funding costs. Since the recalibration of the TLTRO III terms and conditions, which came into effect on 23 November 2022, banks have made sizeable repayments of funds borrowed under the programme. In June, a total of €1.5 trillion (mandatory and voluntary funds) will have been repaid, reducing outstanding amounts by around 72% (compared with the level before the recalibration).[5] Since September 2022 banks have increased issuance of bonds, which are remunerated above deposit rates and the key ECB interest rates, amid the winding-down of the TLTROs and the decline in deposits.

Chart 21

Composite bank funding rates in selected euro area countries

(annual percentages)

Sources: ECB, IHS Markit iBoxx indices and ECB calculations.

Notes: Composite bank funding rates are a weighted average of the composite cost of deposits and unsecured market-based debt financing. The composite cost of deposits is calculated as an average of new business rates on overnight deposits, deposits with an agreed maturity and deposits redeemable at notice, weighted by their respective outstanding amounts. Bank bond yields are monthly averages for senior-tranche bonds. The latest observations are for April 2023 for composite bank funding rates and 14 June 2023 for bank bond yields.

Banks remain well capitalised overall, though developments in funding conditions, interest rate risk and asset quality are likely to weigh increasingly on their lending capacity. Banks continued to increase their profitability in the first quarter of 2023. This was mainly due to their non-interest income sources, while the increase in net interest income experienced throughout 2022 halted amid weak lending growth and broadly stable net interest margins. The turmoil in the banking sector in March led to lower bank share prices and a widening of spreads for more risky bank bonds, such as subordinated bonds and Additional Tier 1 (AT1) instruments. Increased funding pressure as a result of higher deposit rates and large TLTRO repayments are currently weighing on banks’ profitability. With respect to the asset quality of bank balance sheets, non-performing loan ratios have continued to decline but signs of higher credit risks are emerging as the proportion of loans in early arrears has increased, especially for exposures to sectors such as commercial real estate that are more affected by the monetary policy tightening cycle. As regards bank exposures to interest rate risk, unrealised losses on held-to-maturity securities are currently subject to substantial market scrutiny, even though they have been relatively limited so far.